The Ultimate Beer Guide: Everything You Need to Know!

WELCOME TO BEER

Odds are you've had quite a few beers in your life — heck, you may be drinking a nice cold (but not too cold!) brew right now. But be honest with us, and yourself: How much do you really know about beer? If the answer to that question is anything but "I'm a freakin' beer genius and have literally been brewing beer for my entire adult life," then you'll probably get something — hopefully a lot more than something — out of this Ultimate Beer Guide. And trust us, once you know all about beer, drinking it will become a lot more interesting. https://giphy.com/embed/31UAfj25RL6nvarVeK With the enhancement of your beer-drinking enjoyment in mind, let's take a comprehensive, yet manageable dive into the world of beer. In this beer 101 course you'll learn about everything from the history of beer to how beer is made to the different styles of beer to how to store and drink beer. Did that last little lesson get you all psyched? We hope so! We also hope you have a nice IPA in your hand 'cause we're about to get started. Now crack that bad boy open, sip on some of that "learning juice" (as Homer Simpson would call it) and prepare to learn more about beer than you probably have in your entire life. https://giphy.com/embed/RqbkeCZGgipSoWHAT IS BEER?

As always, we need to know exactly what kind of alcohol we're dealing with here, so first up let's talk about what beer is exactly. According to Wikipedia, the hive mind of planet Earth, beer is "one of the oldest and most widely consumed alcoholic drinks in the world... [and] is brewed from cereal grains—most commonly from malted barley, though wheat, maize (corn), and rice are also used." In other words, beer is the product of taking cereal grains, creating a mash out of said grains, adding warm water to the mash in order to create the wort, adding hops to the wort, fermenting the wort/hops combination, taking the booze, CO2, and other byproducts from the fermented wort, maturing it in steel containers, and then filtering it, carbonating it, and (possibly) aging it in a cellar. Now if you're wondering "what is wort," "what are hops," or have any other "what is/are" questions about the description of the beer-making process above, don't panic, 'cause we're going to go into much more detail in the How Beer Is Made section below. But before we get there, let's just knock out a few other quick little tidbits of information about beer's background in case somebody corners you at one of your home parties or giant Oktoberfest celebrations and wants to really test your beer knowledge. https://giphy.com/embed/3o7TKKdv1vyUpyFLva In terms of the biggest highlights from beer's history, the ones you'll want to know off the top of your head in case somebody asks you what you learned about beer while taking this course, those boil down to: beer's discovery/creation in Mesopotamia (what today is geographically Iraq, Kuwait, Norther Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey) around 7,000 years ago, the rise in beer's popularity in Ancient Egypt, beer's widespread production and consumption in the Middle Ages thanks to the horrid quality of water in Europe, the acceleration of the beer production process during the Industrial Revolution, and finally how beer survived the Prohibition Era in America and managed to become, as mentioned above, one of the most widely consumed alcoholic beverages in the world. While the above historical recap is a gross overgeneralization, those are the big moments in beer's story that most broad historical overviews tend to focus on. Obviously there are an uncountable number of caveats, but we'll take a deeper dive into beer's history in the A Very Brief Beer History section below. There you'll learn that beer's original location of discovery is actually debatable, that beer became popular in the Middle Ages thanks to the growth of monasteries just as much to the crappy quality of supposedly potable water, and that the Industrial Revolution helped to speed up and streamline the beer production process thanks to technological innovations such as the glass bottle, the steam engine, and the refrigerator. https://giphy.com/embed/qGLmz4mubDvdC Finally, when it comes to where beer's at in today's world, things are looking extremely bright — like a crisp-ass lager bathed in tropical sunshine. What do we mean when we say that beer's future is extremely bright? Well, the worldwide beer market is expected to be valued at close to $700 billion in 2025. Not only is the beer market likely to increase by about $100 billion compared to its 2017 valuation, it's also undergoing rapid, far-reaching changes thanks to technological innovations and an explosion in the craft beer market. But we'll get into all of that in the Future of Beer section below. For now, let's take a deeper dive into beer's history to learn more about how it went from old soggy bread juice to the glorious drink that we all know and love!A VERY BRIEF BEER HISTORY

Alright, now that we know what beer is, let's find out where it came from and how it evolved over the last nine millennia. We'll start our journey as we've started so many other "history of alcohol" journeys — in the ancient world. This time, in the legendary land of Mesopotamia, a.k.a. "the land between two rivers." Unfortunately those are just two rivers of water, not beer. https://giphy.com/embed/3o6Ztd5vx7mxQ4AkQUTHE DISCOVERY OF BEER IN MESOPOTAMIA (PROBABLY, MAYBE?)

As mentioned above, the exact date and location of where beer was discovered is highly debatable. When you look up the origin of beer's birth, most sources pinpoint the location of Mesopotamia, so that's a fairly safe bet — although it really could've happened in tons of other places around the world, with China being another likely spot. But in terms of when beer was discovered, estimates seem to range between about 10,000 B.C. and 5,000 B.C. In regards to how exactly beer was discovered, that's also up for debate. The problem with pinpointing beer's birth is that it almost certainly happened before any kind of record keeping was the norm. So while there was a 8,000-year-old clay tablet unearthed from the region that was formerly Mesopotamia outlining one of the oldest known beer recipes, there's also speculation that even hunter-gatherers had tasted beer on their prehistoric tongues thousands of years earlier. This is because beer, or at least what could be considered a boozy predecessor to beer, can be made accidentally just by leaving a bunch of fruit out in a basket to grow old and self-ferment. Spontaneous fermentation can also happen with cereal grains thanks to wild yeasts in the air. (Mama Nature really likes making it easy to discover booze, right?)

An image of a dated and signed beer receipt from Sumeria (2050 BC). Image: Wikimedia / Dr Tom L. Lee

But because one of the earliest known records of beer was that recipe tablet written 8,000 years ago in Mesopotamia (specifically the northern region of Mesopotamia known as Sumer), we'll go ahead and go with that as the true birthplace of beer. Plus, Sumerians were using beer as a form of currency during that time as well, so you know they knew how good that ish was. On top of that beer recipe tablet, the Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest known written law "documents" from Mesopotamia, also lays out specific regulations for beer and taverns that served beer. Although the Code of Hammurabi is much younger than that first beer recipe clay tablet, dating back to about 1754 B.C. Regardless of exactly when and where beer was first discovered/created, one thing is certain: Beer is deeply and inexorably linked to human history since we've had settled agricultural societies (at least). But you know who undoubtedly really really loved beer? The ancient Egyptians.BEER IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Next up on our history of beer world tour, we arrive in ancient Egypt (around 3,000 B.C.), where ancient Egyptians really started to go goo-goo for that brew brew. It was here that beer became so intertwined with culture that it was carved into wood and stone inside of tombs, used for medicines and in religious ceremonies, and supplied as a daily ration for the slaves building the Great Pyramids at Giza. Even Ramses III, one of Egypt's most well-known pharaohs, enjoyed beer so much that he and his cohort would drink it from gold cups.

Egyptian model of beer making in Ancient Egypt. Image: Wikimedia / E. Michael Smith Chiefio

Egypt was also the civilization that introduced ancient Rome to beer, although they preferred wine to beer and actually thought the latter was only for barbarians. Also, ancient Rome eventually conquered ancient Egypt and after that, beer was basically supplanted by wine.BEER IN THE MIDDLE AGES

Our next big stop on our tour isn't really a place, it's a time: the Middle Ages. It was during this period that beer began to be consumed daily by all social classes, especially in areas where it was difficult to make wine due to poor grape cultivation opportunities. Beer became so popular because it wasn't only relatively cheap to make, it was also often safer to drink than water. Although according to some historians it's a myth that beer was a more common drink than water. It was still definitely safer though because water used for beer had to be boiled, which killed off bad bacteria. The Middle Ages also saw the spread of Christianity, which was important for the spread of beer because monks in monasteries began to mass produce it. (Side note: It was women producing all the beer before, especially in Egypt.) Monasteries were producing so much beer, in fact, that in some ways they could be considered the first commercial breweries. Monks were allowed to sell their beer, which they referred to as "church ales" in what were called "monastery pubs," and also offered free beer to the lower classes (peasants...) during feasts and celebrations. Oh, and they also pounded down plenty of the stuff themselves. https://giphy.com/embed/TgFv7gGhIy1Ne Although monasteries helped to spread beer-drinking culture all throughout Europe, it wasn't until the mid-fourteenth century that beer became truly ubiquitous. It was during this period (from the mid-fourteenth century until the early seventeenth century) that major commercial beer breweries came online, and consumption amongst the masses grew enormously thanks to broad increases in income. Traveling merchants became more and more popular, which resulted in more and more taverns and inns, which, in turn, resulted in more and more beer!SIDE NOTE: HOW HOPS ENTERED THE PICTURE:

A handful of California hops. Image: Flickr / srdryja

Before being used in beer, hops were used as a medicine to help people calm down, or go to the bathroom thanks to its laxative properties. But once it was discovered that hops could help to balance out the flavors of the sweet, malt beer being produced during the period, as well as help beer to last longer as it was moved around, it soon became a staple ingredient of beer recipes across Europe. And if you're wondering how exactly hops went from some random flowers people used to help them calm down or poop to being a key ingredient in beer, we're sorry to tell you that historians don't really know. Maybe somebody who loved beer was really "backed up" and decided to add some hops to their favorite drink?BEER DURING THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

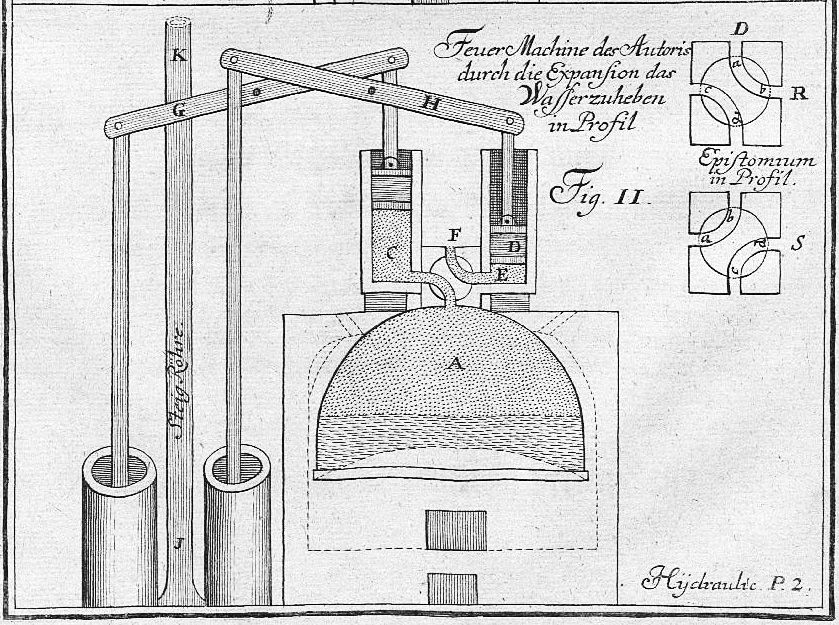

Now we leap from the Middle Ages to another period in history, the Industrial Revolution, a much shorter span of time that saw a lot more growth for beer thanks to innovations like the steam engine and the refrigerator. These types of innovations allowed for the industrialization of the beer industry (that Industrial Revolution doing it's thing), which led to a sharp increase in beer production and consumption toward the end of the 19th century. By the early 20th century, beer markets in Germany, the UK, and the U.S. had ballooned to about 2 billion gallons produced and consumed in each market. Here's a quick rundown of the major Industrial Revolution innovations that affected the world of beer: The steam engine — The steam engine massively improved the efficiency and output of breweries by mechanically pumping water, wort, and beer, by stirring the mash and grinding the malt, and by raising casks out of cellars. The steam engine also obviously helped with tons of other aspects of the beer industry, like transportation, for example.

A diagram of one of the first-ever steam engine. Image: Wikimedia / Leupold, Jacob

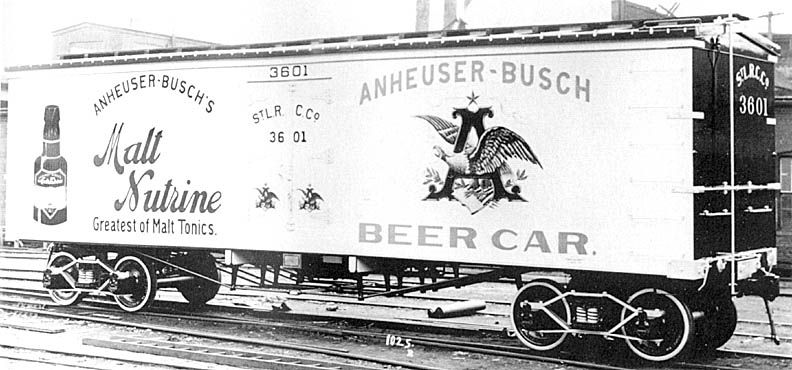

The mechanical refrigerator — The mechanical refrigerator helped to revolutionize the beer industry for a bunch of reasons, which makes sense as it was actually first invented with the intention of aiding the brewing industry. (In 1873 Carl von Linde invented mechanical refrigeration while working for the Spaten Brewery in Munich.) The new refrigeration technology allowed brewers to brew their beer year-round rather than in just the winter months; this was the case because yeast requires certain temperatures to work, and without refrigeration, it would've just died off. Fermentation is an exothermic process, which means it releases a lot of heat; without refrigeration that heat would kill off the bacteria. Because breweries no longer needed cold caves or fresh ice carved from chilly rivers, they were suddenly allowed to pop up pretty much wherever they wanted to. Mechanical refrigeration also allowed for lagers, which require colder temperatures for proper fermentation, to become just as produceable as ales.

One of the first railroad refrigerator cars; this one operated by Anheuser-Busch. Image: Wikimedia / Creative Commons

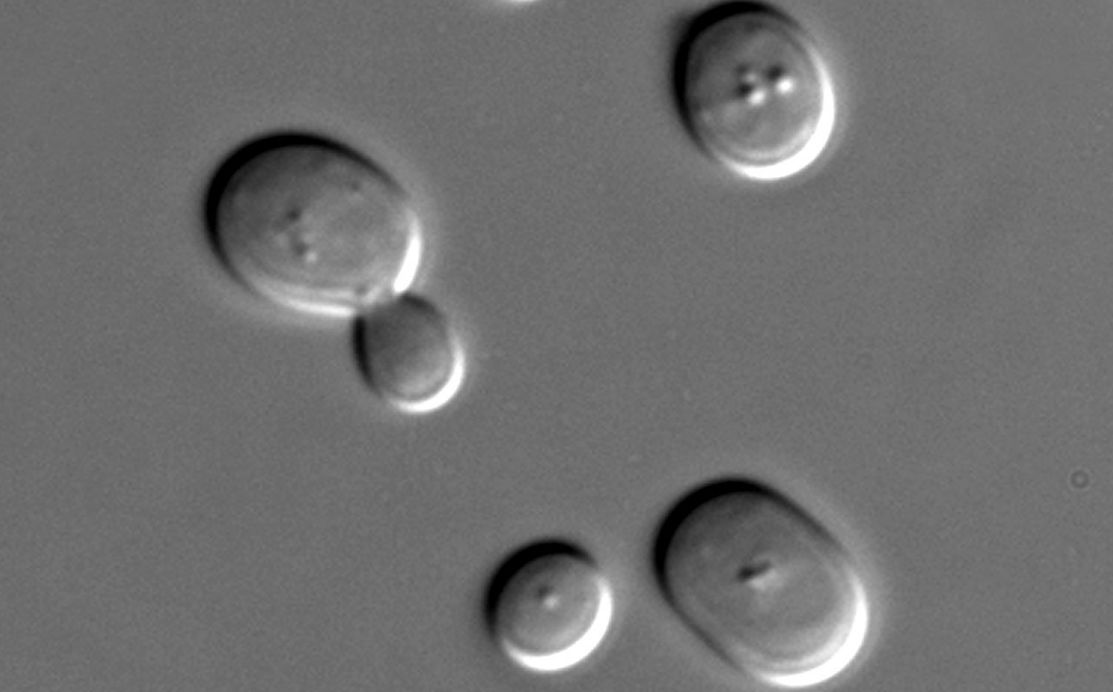

Mechanized assembly of glass bottles — Before glass bottles and beer cans, beer was commonly stored in and served from oh-so-sophisticated containers like buckets and leather sacks. This obviously wasn't the best way to store beer for about a million reasons, but glass mechanized glass bottle assembly lines changed all that during the Industrial Revolution. This new way of making beer bottles brought the cost of production down enormously, allowing beer bottles — and all of the beautiful utility of beer bottles — to finally become ubiquitous. Light, sturdy beer cans — Ever try transporting beer in bottles in rickety trains, cars, or even worse, horse carriages? Yeah, you're going to get a lot of bottle breakage and a lot of lost profits. Not with beer cans though, hence the invention of beer cans and the "keg-lined" steel container. These inventions changed the way breweries would transport much of their beer. Advanced yeast knowledge — Even though yeast had been used to make beer since making beer was a thing, it wasn't until the 19th century that scientists and brewers began to understand that these single celled organisms were responsible for fermenting malted barley water. Until then, it was just kind of beer working its magic. The specific game-changing breakthrough in yeast understanding took place thanks to Louis Pasteur demonstrating that yeast was actually made up of single-celled organisms that were turning fermentable sugars into ethanol and a bunch of other byproducts.

Microscopic close-up of yeast cells. Image: Wikimedia / Masur

The creation of the "lagering" process — Although lager (which is German for "storage") was being produced before the 19th century in Germany, it wasn't until the Industrial Revolution that it was able to be produced year-round and on a large scale. That's because lagers use a "bottom fermentation process," which requires colder temperatures. And remember how we mentioned the invention of the refrigerator and how it allowed brewers to make beer year-round? Yeah, that was a big deal for making lager a sustainable, cost-effective beer to produce.BEER IN THE MODERN WORLD (WITH A FOCUS ON AMERICA)

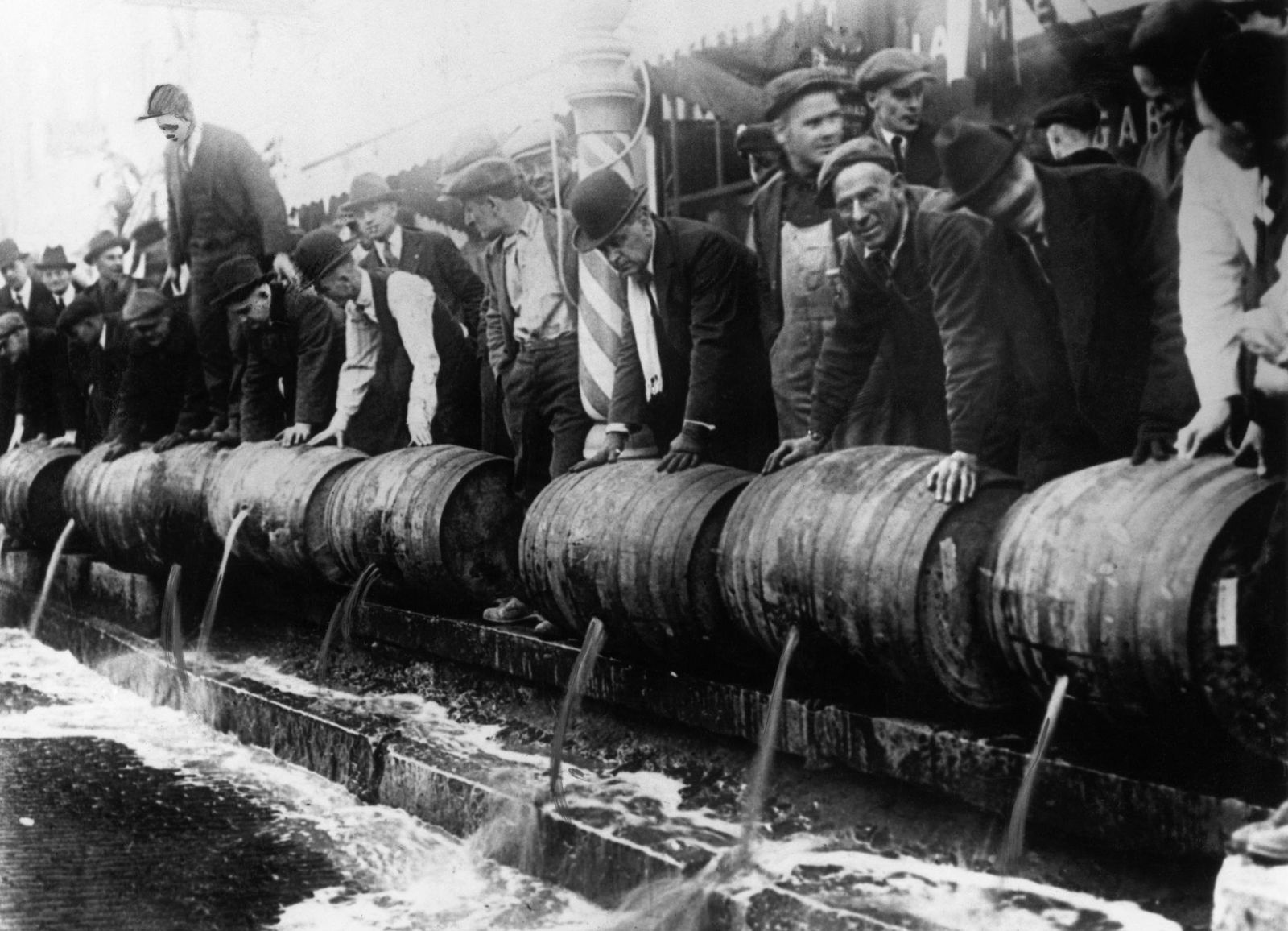

Barrels of beer emptied into the sewer by authorities during Prohibition. Image: Flickr / Tullio Saba

After World War II the American brewing industry underwent an enormous wave of consolidation. Larger breweries started buying up smaller ones for their distribution systems and customer bases, and would subsequently shut down their actual breweries. This consolidation resulted in the behemoth conglomerated breweries that we're familiar with today (e.g. Anheuser-Busch). As a fun side note, you can check out a graph of the number of breweries in the U.S. over time thanks to the Brewers Association. Following the graph, you can see the number of breweries in the U.S. start to nose dive in the beginning of the 20th century, fall to exactly zero during Prohibition, then eventually climb back up to roughly 6,400 in 2017. That climb from zero breweries back up to roughly 6,400 in 2017 saw a lot of twists and turns for the beer industry as a whole though. As mentioned, it wasn't a continuous climb from zero back up to the thousands of breweries that are now in existence in the U.S. Due to the aforementioned consolidation trend, the number of breweries remained low for quite some time before beginning to climb steeply again. Then, starting around 1980, other alcoholic drinks, particularly wine, began to increase in popularity and pull consumers away from the beer market, resulting in a per capita decrease in consumption in the U.S. Although total production in the U.S. still continued to increase thanks to overall increase in population.

An inside look at the certified-independent Allagash Brewing Company in Portland, Maine. Image: Flickr / Allagash Brewing

Fast forwarding to today, we see a huge explosion in the popularity of the craft beer movement in the U.S. In fact, in 2013, only 55 of the 2,538 operational breweries in the U.S. were non-craft. Along with an explosion in the popularity of craft beer (also known as beer made by "microbreweries") in the U.S., other major changes in the beer industry have also occurred. Starting in the second half of the 20th century, there has been a shift in the growth of global beer markets away from developed countries like the U.S. toward developing countries such as India and Brazil. China, for example, has become the largest beer market in the world. Diet beers, most often termed "light" beers, also increased enormously in popularity in the U.S. in the second half of the 20th century, although the craft beer movement obviously offered plenty of not-so-light beers in response.

HOW BEER IS MADE

You now know what beer is and have enough beer history knowledge crammed into your brain to help you sound like a total know-it-all at your local dive bar, so what's next? Learning about how beer is made! And even if you think you know all about how grains become those tasty suds that refresh your buds, we promise that reading through the following steps will, at the very least, help to refresh your memory.MALTING

The first step in the beer-making process is known as malting. OK, technically the first step would be to gather your grains — such as wheat, rye, or barley — but once that's been done, it's time to malt said grains. What is malting exactly? Good question! Malting is the process by which grains are encouraged to sprout then subsequently dried out in order to isolate the enzymes Basically what’s happening during this step is the encouragement of grain seeds to germinate, or catalyze the process of becoming a plant. Producers want the seeds to germinate because during this process the enzymes required to turn the seeds’ starches into soluble sugars (maltose) are created. (If you want to go really deep into the science here, this page is perfect.)

Germinated barley ready to be ground down into grist. Image: Wikimedia / Finlay_McWalter's friend SJB

In order to induce germination, the grain is soaked in warm water for around two to three days, and then spread out on the floor of a malting house. In the malting house, the grain is regularly turned by dudes with shovels to maintain a consistent temperature — sometimes big turning barrel machines perform this function as well. Once the grain has released the enzymes necessary to turn its starches into soluble sugars, the germination process is halted with heat. These starches will be turned into soluble sugars during the next step, which will be turned into (oh so lovely) booze during the fermentation step.MASHING

Once you’ve ground down your malt with a mill into what’s called a “grist” — a bunch of dried, de-husked seeds that have germinated — you’re ready to mash. In this step, the grist is mixed with warm water in giant insulated containers called mash tuns. Inside the mash tuns, the warm water encourages the enzymes in the grist to break down its starches into soluble sugars. These soluble sugars are extracted from the seeds and pulled into the warm water (thanks to all that heat), and the result is a sugary, non-alcoholic liquid known as “wort.” The wort is then strained and drained out of the bottom of the mash tuns. Side note: There are varied processes for mashing, e.g. decoction mashing, which takes a portion of the grains from the grist, boils them in a separate tun, and then returns them to said grist to raise the overall temperature inside the mash tun. Infusion mashing, on the other hand, only has the grains boiled in a single mash tun.

From left to right: a mash tun/boiling kettle, a whirlpool, and a lauter tun. Image: Flickr / Christer Edvartsen

SUB-STEP: LAUTERING

Let's get into the weeds real quick here and talk about lautering, which is an important step that isn't usually included in general beer-making overviews. Basically, lautering is the process by which the fermentable wort is separated from the spent grain — i.e. all the stuff that's left over from the milled and mashed grains that won't be used to make booze. This separation usually takes place in a separate lauter tun (pictured below), although that's not always the case. The lautering process happens in three steps, including mashout, recirculation, and sparging. The mashout step raises the temperature of the wort to 170 degrees Fahrenheit to stop the grains from producing enzymes while preserving the fermentable sugars in the wort. The recirculation step involves drawing the wort out from the bottom of the lauter tun then sending it back through once more to filter it again. And finally the sparging step rinses the remaining spent grain in the lauter tun with warm water to get as much of the remaining fermentable sugars out of it as possible.

A glimpse at the sparging process. Image: Wikimedia / cogdogblog

BOILING / HOPPING THE WORT

At this point in the process, the wort is boiled for about an hour while hops and various other spices are added. The heat from the boiling process provides sterilization, and the hops provide a bitter flavor to help balance out the natural sweetness of the sugar-rich wort. But wait — what are hops again?WHAT ARE HOPS?

The most basic definition of hops you'll get from Wikipedia is that they're "the flowers (also called seed cones or strobiles) of the hop plant Humulus lupulus." Wikipedia also notes that they're "used primarily as a bittering, flavouring and stability agent in beer, to which they, beyond bitterness, impart floral, fruity or citrusy flavours and aroma." It's that second part we're concerned with when it comes to beer, because, as you can deduce by now, if you didn't have hops in your beer recipe, it would be dang sweet. Not too sweet to drink at all — remember that plenty of beer had been drunk before hops became a beer thing in the 11th century — but still definitely not the beer you're used to tasting.

Humulus lupulus plant from which hop flowers are taken. Image: Flickr / Matt Lavin

The effects hops have on a beer's flavor profile varies, but they can generally be divided into two categories: bittering and aroma. Bittering hops are generally responsible for — you guessed it! — bittering the beer. Aroma hops, on the other hand, are usually used to help finish the beer; they're literally added toward the end of the boiling period, and provide, you guessed it again, various pleasant aromas. In terms of how exactly adding the little hops to the wort makes it more bitter, that's all thanks to the alpha acids, beta acids, essential oils, and flavonoids released by the hops as they're boiled. Alpha acids are what make the beer bitter, beta acids are actually detrimental to the beer and usually neutralized as much as possible, essential oils give beer their signature hoppy aroma, and flavonoids help to protect and stabilize the beer. As a little side note, hops aren't always added during the boiling step. There is a process called "dry hopping," which has the hops added toward the end of the fermentation cycle.SUB-STEP: FILTRATION BY WHIRLPOOLING

Like the lautering step, whirlpooling also aims to clarify the wort by removing hop solids and other proteins, which are collectively known at this point as trub. Many, but not all, brewers will use a separate vessel for the whirlpooling step, known as a whirlpool, which uses centripetal forces to collect the trub in a cone in the bottom of the vessel. Some brewers will use a vessel called a hopback instead of a whirpool, which uses fresh hop flowers or cones to filter the trub.

Trub at the bottom of a fermentation container used for homebrewing. Image: Wikimedia / Nimmolo

FERMENTATION

Now that the wort has been made and boiled and the hops have been added, it's time to release the yeast! Yeast, a single-celled fungus, is added — or pitched, which is common brewer's term for adding yeast — to the hoppy wort once it's been put into a fermenting vessel. Once the yeast has been added, the temperature of the beer (wort and yeast combination) is held in a range between 60 and 68 degrees Fahrenheit for ales and 50 degrees Fahrenheit for lagers.

Yeast turning fermentable sugars into ethanol and CO2. Image: Flickr / David Burn

Speaking of ales versus lagers, recall from the A Very Brief History of Beer section that lagers became popular much later than ales because they required a different type of fermentation process. Here is a quick breakdown of the yeasts/fermentation processes used for each type of beer: Top fermenting — Yeasts used for making ales are known as "top fermenting" because they rise to the surface of the fermentation vessel during the fermentation process, resulting in a rich, thick head of yeast. Top fermenting yeast strains are also introduced at higher temperatures than those used for lagers — 50 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit versus 44.6 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit, which results in beers that are higher in esters. Top fermenting yeasts are used for making wheat beers, porters, stouts, Altbier, Kölsch, etc. Bottom fermenting — Yeasts used for making lagers are known as "bottom fermenting" because they tend to settle on the bottom of the fermentation tank as the fermentation process peters out. Bottom fermenting yeasts are used for making lagers including American malt liquors, Pilsners, Dortmunders, Märzen, and Bocks. Anyway, with either fermentation process, basically what's happening is the yeast is munching on the fermentable sugars and turning them into ethanol (a.k.a. alcohol that gets you tipsy) as well as carbon dioxide and a few other byproducts.

Fermentation tanks (note this is one type of setup, there is a lot of variance). Image: Flickr / Mats Lindh

Side note: Beer can also undergo "spontaneous fermentation," if it's left out and exposed to natural/wild yeasts and bacteria in the air. Beers resulting from this kind of fermentation are usually sour, and obviously not filtered at all. And while it may seem like no brewer in their right mind would make beer this way, this is indeed how some beers are made in Belgium.AGING / CARBONATING / BOTTLING

OK, now that the grains have been milled and mashed, the wort has been boiled and combined with hops, and all of that sugary goodness has been fermented into good ol' booze, carbon dioxide, and a few other organic compounds, it's finally time to condition, age, and bottle the beer. So let's break down those three steps real quick: Aging — When it comes to aging beer, you're not talking about anything serious like you would be with something like whiskey, where it could sit in caskets for decades on end. Some aging does often happen however, especially with the lagering process, which calls for lagers to be stored at or below cellar temperature (50-55 degrees Fahrenheit) for anywhere from one to six months. And while aging beers is generally associated with the process used for making lagers, it can also be used for making ales. In either case, aging helps a beer's taste by eliminating various detrimental chemicals, acids, and compounds.

Beer conditioning tanks at the Anchor Brewing Company in San Francisco, CA. Image: Wikimedia / Picardin

Carbonation – When it comes to carbonating beer, there are basically two methods used: allowing the beer to carbonate in the bottle thanks to yeast continuously producing CO2 even after the beer has been bottled, or "force carbonating" the beer, which works by pumping CO2 into the beer bottle under high pressure, forcing its absorption into the liquid. Most beer makers use the latter method because it's much faster and results in more clarity in the beer. Bottling — Here it is people, the final step on our brief beer-making journey! This is the point at which beer is actually put into the bottle or the can, although to eliminate any confusion, keep in mind that the bottling process happens more or less concurrently with the carbonation process — natural carbonation in the bottle or forced carbonation in the bottle both happen after the beer has been bottled (duh). Once the carbonation step is finished, the beer is shipped off, stocked in restaurants, markets, and liquor stores, and ready to be consumed!THE DIFFERENT TYPES/STYLES OF BEER

A TINY TINY HISTORY OF HOW BEER STYLES CAME TO BE

Before jumping right into beer styles, you all will probably want to know where they come from. And no, sadly, it's not Dionysus' uncle Coltus45. In fact, if you're looking at the worldwide picture, it's really difficult to keep things straight as there aren't any internationally recognized universal categories and styles for beer. There is Michael Jackson though — although not that Michael Jackson. Michael Jackson — again, not that Michael Jackson — was a British writer and journalist who wrote a bunch of books about beer and whiskey, and pioneered the idea of different beer styles. With his 1977 book, The World Guide To Beer, Jackson laid the groundwork for the general beer style differentiations that even the finest of connoisseurs use today. Wikipedia notes that "The modern theory of beer style is largely derived from this book, in which Jackson categorised a variety of beers from around the world in local style groups suggested by local customs and names."

The legendary beer categorizer, Michael Jackson. (Again, not that Michael Jackson.) Image: Wikimedia / Päivi Kuusjärvi

Even though Jackson is credited with laying out all of the differentiate beer styles that people use around the world today, differentiating between beers is as old as beer itself. And we all remember how freaking old beer is from the above beer history section. Beer categories are so old, in fact, that there was a receipt for the "best" ale found in Ur (a Sumerian city in Mesopotamia) that dates back to 2050 BC. Beer history is also littered with various other individuals and societies categorizing beer throughout the ages. The Hittites, a people who inhabited Anatolia (Asia Minor) around 1,600 BC had at least 15 types of beer; Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and naturalist who lived around 50 AD, wrote about Celts making an ale "in Gaul and Spain in a number of different ways, and under a number of different names"'; the Anglo-Saxons — people from Germany who inhabited Great Britain around the 5th century AD — even had laws identifying different types of ales.LAGERS VS. ALES

Categorizing beer is always going to start with two big umbrella categories: lagers and ales. What's the difference between the two? One uses one type of yeast, the other uses another type of yeast. That's it. Kind of. Because the two different yeasts (Saccharomyces cerevisia for ales, Saccharomyces uvarum for lagers) require different temperatures to thrive and ferment, the resultant beer of their respective fermentation processes are different in taste and aroma. Although this isn't the only factor that affects the flavor profile and aroma of the beer — the malt bill, as well as (sometimes) added fruit and spice additives are key to the makeup of the beer's final flavor and aroma, and the malt bill directly determines the final color of the beer. So even though you may always think of lagers as light and ales as dark, plenty of light ales exist (e.g. blonde ales), and plenty of dark lagers exist (e.g. dark lagers).

A brown ale (left) versus a bock lager. Images: Flickr / Steven Penton; Flickr / Marco Verch

For the very broad strokes, here are the differences between the two beer categories: Ales — Ales are usually darker and cloudier. They also usually have a higher alcohol content and more in-your-face flavors marked by fruitier flavors and bitter tones. As we learned earlier, these bitter tones come from adding more hops relative to lagers. Lagers — Lagers are usually lighter in color, clear, and lower in alcohol content. They also usually tend to be sweeter and smoother than ales, and finish with a distinct crisp flavor. These characteristics stem from lagers' higher sugar content, slower, colder fermentation process, as well as the type of yeast used. Plus a few other factors like post-fermentation handling and flavoring.LAMBIC BEERS (A CAVEAT)

OK, so there only being two major umbrella categories for beer is a bit of a lie. But only a bit. Because there's a third beer type you'll probably come across at the liquor store and that is a lambic beer; a type of beer brewed in the Pajottenland region of Belgium and in Brussels itself at a single distillery. Lambic beers are distinctive from those in the other two categories because of, again, the type of yeast used. Except in the case of lambic beers, the yeast isn't placed in a vessel along with the wort, instead the wort is cooled overnight in a wide, shallow pan that kind of looks like a small copper pool — known as a coolship — where it's exposed to 120 different types of microorganisms and wild yeasts that are just flying around in the air! Once the wort has been exposed to the wild yeasts and other microorganisms in the air, it's then moved into oak or chestnut barrels where it's aged — and further fermented by the yeasts in the wood — for years on end. Many lambics are aged for one to three years, although, as with whiskey, aging times can span decades.

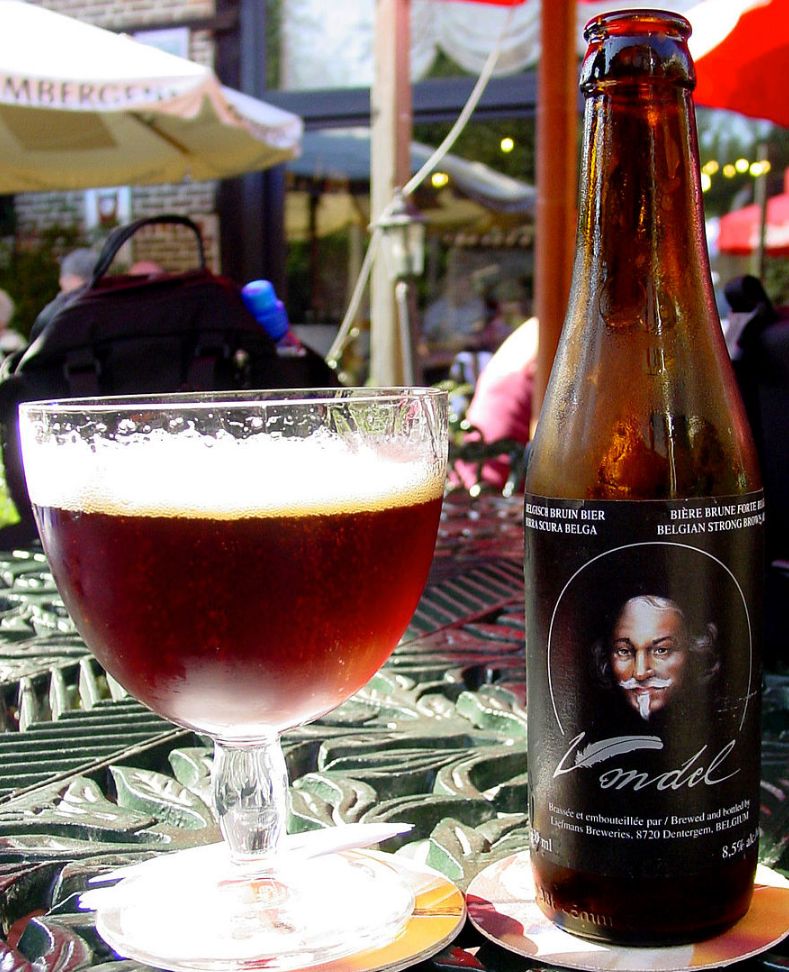

One example of a lambic beer from Belgium. Image: Wikimedia / Jon Sullivan

Fruit flavoring is also often added to lambics as well, although it's not a requirement. Some of the most popular fruit flavors include raspberries, apricots, grapefruits, muscat grapes, cherries, etc. These fruity flavors help to balance out the distinctly sour flavor profile that's typical of most lambics. Also, speaking of flavor profiles, lambic's character is distinctive from other beers as it's not nearly as carbonated, much cloudier, thicker in terms of mouthfeel, and generally more "funky" tasting.THE DIFFERENT BEER STYLES

Now that we have Ales vs. Lagers cleared up, as well as a little side note on lambic beers, let's dive into a bunch of the different styles that you're bound to see on shelves wherever beer is sold. ALTBIER Altbier is a German-style Brown Ale. Altbiers are traditionally conditioned for a longer period of time versus other beers, hence the name; Altbier literally translates to "old." The longer conditioning period mellows out the ale's fruitiness and also results in an incredibly smooth, delicate, clean beer. Altbier's color ranges from dark brown to amber, is moderately carbonated, and usually has a spicy, herbal flavor profile. AMBER ALE Amber ale is a term that's used in Australia, North America, and France, and refers to pale ales made with amber malt and sometimes crystal malt, producing a beer that generally ranges from light copper to light brown. In terms of the flavor profile of amber ales produced in the U.S., they're usually a balanced blend of hop and malt flavors with notes of caramel. BARLEY WINE (OR BARLEYWINE) Barley wine is a style of ale that's usually between 6 and 12% alcohol by volume. In fact, barley wine gets its name from the fact that it has a similar ABV to wine. It is typically released once a year in the U.S., during autumn or winter, and ranges in flavor from dark fruit to quite hoppy.

One example of a barley wine beer. Image: Flickr / Christer Edvartsen

BERLINER WEISSE Berliner Weisse is a cloudy, sour beer with a fairly low ABV of about 3%. It's a variation of the white beer style produced in Northern Germany, and dates back to at least the 1500s. In terms of flavor profile, it's tart, acidic, and often reminiscent of sparkling wine. BIÉRE DE GARDE Bière de Garde is a strong-tasting pale ale that's produced in France. Bière de Garde was originally made in farmhouses — this style of beer can also be referred to as a "Farmhouse ale" — during winter and spring. Character-wise, Bière de Garde tends to be golden or copper in color, with flavor intensifying in accordance with a more intense color. Flavor-wise, this beer type offers a toasty profile that often has notes of toffee, biscuits, and caramel.

One example of a Biere de Garde. Image: Flickr / Hungry Dudes

BITTER Bitter beer is a British style of pale ale that has an ABV of around 3-7% and ranges from gold to dark amber in color. In terms of flavor profile, it can vary greatly, although these beers often have a fruity aroma with a hoppy, bitter taste on the tongue. BLONDE ALE Blonde ale is a pale colored ale that usually has an ABV ranging from around 4-6%. Blonde ales generally don't have too much in common except for their color, although they usually have a crisp, clear, dry finish. The also have a lighter body thanks to higher level of carbonation, as well as a fairly restrained range of bitter notes mixed with sweetness from the malt. BOCK Bock is a strong, German lager that ranges in color from light copper to brown. In general, Bock is stronger than other lagers, with a more pronounced malt flavor. There are also usually strong notes of a hoppy bitterness, although it doesn't overpower the sweeter malt flavor. Doppelbock Doppelbock is a sub-category of the Bock lager. It is characterized by malty sweetness and a relatively subdued hoppy bitterness. ABV is usually around 7-8% and the color ranges from amber to dark brown.

One example of a doppelbock. Image: Flickr / Bernt Rostad

Helles Bock / Maibock Helles bock — also often referred to as maibock — is another sub-category of bock lagers. The respective German names translate into English as "Pale Bock" or "May Bock," the second name hinting at the fact that this is a seasonal (springtime) beer. In terms of character, Helles bock/Maibock beers are usually about 6-8% ABV, and are generally paler and more hop-centric than other Bock beers. They also usually have a malt-heavy, spice- and pepper-infused flavor profile. Weizenbock Weizenbock is a wheat variation of Bock with a flavor profile marked by dark fruits like plums, grapes, and raisins. Weizenbocks usually have an ABV of around 7% and are generally considered to be a combination, in terms of overall character, of hefeweizens and doppelbocks. Eisbock

One example of a cream ale. Image: Flickr / Chris Waits

DORTMUNDER / DORTMUNDER EXPORT Dortmunder — which is also referred to as a Dortmunder Export or an "export lager" — is a pale, German lager that combines the malt-forward sweetness of a Helles bock with some of the bitter tones of a Pilsner. In general, Dortmunders have a higher ABV than other pale lagers (around 6%). The name comes from the German city where the beer was first brewed, Dortmund. DUNKEL Dunkel, which literally translates from German to "dark," is a term used to describe several types of German lagers. Dunkel beers usually range from amber to dark reddish brown in terms of color, and are notable for their smooth, malty flavor. In general, if you order a dunkel beer at a bar, you're basically asking for whatever dark beer is currently on tap. Dunkels are also considered to be the forerunners to the modern-day German pale lagers.

One example of a dunkel. Image: Flickr / Christer Advartsen

DUNKELWEIZEN Dunkelweizens mix up the fruity/spicy flavor profile of a hefeweizen with the rich malt character of a Munich dunkel. Color-wise, Dunkelweizen ranges from light copper to dark brown, and in terms of flavor profile, offers notes of clove, banana, and other fruity esters. Dunkelweizens are also usually full bodied, creamy, and relatively low in bitterness. FLANDERS RED ALE Flanders red ale is a style of sour ale brewed in Belgium that tends to range from burgundy to reddish brown in terms of color. In terms of flavor profile, Flanders Red Ale tends to be distinctly tart, fruity, and light-bodied. Flanders red ales are considered to be very complex beers, thanks in large part to specialized yeast strains, long-term aging in oak casks, and the blending of young and old beers. ABV-wise, you can expect most Flanders red ales to range between 5 and 7%.

One example of Flanders Red Ale. Image: Flickr / Dirk Van Esbroeck

GOSE Gose is an ale that's unlike most other beers because it's made from half malted barley and half malted wheat, as opposed to only malted barley. Gose is also distinctive for a few of other reasons, including the fact that it's fermented with lactobacillus bacteria (which gives it a distinctive sourness), the fact that it's very low in hop character (coriander is usually added instead of hops, which lends spicy and lemony flavors), and the fact that it's brewed with salt. Gose beer generally has an ABV of somewhere between 4 and 5%, and is usually medium yellow to deep gold in color. GUEUZE Gueze is a type of lambic beer made in Belgium. It's made by blending younger lambics with older ones (one-year-olds with two- to three-year-olds), the combination of which is then bottled for a second round of fermentation. Due to this unique fermentation process (even among the already unique fermentation process of lambic beers in general), Gueuze beers taste even more distinctive from traditional ales and lagers. Gueuze beers are often described as very sour and even "barnyard-like," and due to their high level of carbonation are sometimes referred to as "Brussels Champagne." In fact, Gueze is even served in small champagne bottles.

One example of a gueze. Image: Wikimedia / Gordito1869

HEFEWEIZEN Hefeweizen is a German wheat beer — "hefe" means yeast in German and "weizen" means wheat. Flavor-wise, Hefeweizens offer a wide range of flavors including notes of vanilla, cloves, bananas, and even bubblegum. Traditional German hefeweizens are also not hoppy at all. Character-wise, Hefeweizens are usually unfiltered, with settled yeast at the bottom of the bottle as well as an overall cloudy and pale appearance. Also, as you've hopefully guessed from the name, hefeweizens have a mash bill that's usually made up of about 65% malted wheat. The other 35 or so percent is usually malted barley, a mash makeup that helps to deliver refreshing crispness and a light body. Side note: There are German Hefeweizens (the real OG stuff) and American Hefeweizens (not so OG). Typically, American Hefeweizens are more hoppy than their German counterparts, use less wheat in the mash, and also utilize American yeast strains that give them a more malt-forward flavor profile.

Some examples of Hefeweizen beers. Image: Wikimedia / Ich

INDIA PALE ALE Here's a beer you're going to come across a lot on your journey through the land of brew: India Pale Ales (IPAs). IPAs are a type of extra hoppy ale that has become extremely popular with craft brewers. Although its exact origin as a distinctive style is somewhat debatable, it seems that many industry experts agree that it was made in order to be shipped from England to India during the 19th century when the latter was a colony of the former. The sea voyage from England to India would've taken months at that time, and the thinking is that all of the extra hops were added to help stabilize the beer and make sure it would last until it arrived at its destination. Surprisingly, the added hops not only helped to stabilize the beer, but also to change its flavor profile in a way that many British soldiers found quite pleasing.

One example of an IPA made in the U.S. Image: Flickr / Edwin

Flavor-wise, IPAs are often considered to be an acquired taste 'cause they're so dang hoppy, i.e. crazy bitter. Aside from that flavor constant, you can also expect IPAs to consistently boast floral, earthy, piney, citrusy, and fruity flavor notes as well. So really, if you can get past all that bitterness, you're in for a world of flavor with IPAs. You're also in for a decent amount of alcohol as well, as the ABV on IPAs usually ranges from 6-7.5%. Although the IPAs make up their own category of ale, they are themselves further divided into subcategories, some of which are listed below: English Style IPA The English IPA is the OG IPA (something you could probably glean for yourself based on the brief little IPA history above). English IPAs tend to have a flavor profile that's less hoppy than American style IPAs, and are also marked with moderate to strong fruit flavors. English IPAs also usually have a lower ABV relative to American IPAs, are generally gold to copper in color. American Style IPA American IPAs — which are somewhat responsible for reviving the whole IPA style — have strong hop flavors (intense bitterness...), significant notes of citrus and herbal flavors, and an ever-present malty background. As mentioned above, American IPAs usually have a higher ABV range than English IPAs, with a range of 6.3-7.6% for the former and 4.5-7.5% for the latter.

One example of an American style IPA. Image: Wikimedia / SteveR

Imperial (Double) IPA Imperial IPAs are basically the most hard-hitting style of IPA in terms of bitterness and ABV. Although "Imperial" originally connoted beer that was brewed in England and subsequently shipped to Russia, it's not synonymous with "big and bold." If you see the word "Imperial" on a beer label, prepare for two to three times the normal amount of hops and malts used during the brewing process, as well as an especially high ABV. In the case of IPAs, if you're picking up a bottle of something that's been labeled "Imperial," expect it to be extra bitter and extra boozy — on the order of 10 to 12% ABV. Session IPA Session IPAs, at their core, are about two things: lots of IPA hoppy goodness, and a fairly low ABV — hence the term "session," as in you can sit down and have a little drinking session with these bad boys and be OK 'cause they don't have too much alcohol in them. (Session IPAs usually have about 3.2-4.6% ABV.) KÖLSCH Kölsch is, you guessed it, another German beer. It's distinctive from many other German beers, however, as it is warm fermented with ale yeast, then cold-temperature conditioned like a lager. (There are other German beers that use this hybridized process, including many central European beers like Düsseldorf's altbier.) Because of this combination of both ale- and lager-making processes, Kölsch is considered a "hybrid beer." Flavor-wise, Kölsch tends to be light, sessionable, with a crisp, clean finish common for pale lagers. This is one of the best warm-weather beers. Kölsch beers usually have a gold-ish yellow color.

One example of a Kölsch beer. Image: Wikimedia / Gordito1869

MALT LIQUOR The term "malt liquor" was actually first used in the 17th century in England, but for all intents and purposes, if you hear the term, just think of cheap beer made in North America that's usually around 6-9% ABV. Malt liquors are able to achieve this higher range of the ABV spectrum by using heartier strains of yeast and a more fermentable sugar-heavy malt. Flavor-wise, malt liquor usually has a light, pale amber color, a little bit of hops bitterness, and a strong, yet not overwhelming range of sweet flavors. MILD ALE Mild ale is a mildly hopped ale that originated in Britain in the 1600s or earlier. Most mild ales on store shelves today are usually dark in color with a low ABV of around 3-3.8%. There are some exceptions to this norm, with some mild ales having a lighter color and/or an ABV of around 6%. Light mild ale is similar to regular mild ale, although it's paler in color. In terms of flavor profile, mild ales offer notes of toffee, caramel, chocolate, and nuts, with hints of fruit, like raisin or plum. It has a dry or sweet finish and is obviously very sessionable with that low ABV.

One example of a mild ale. Image: Wikimedia / LeeKeoma

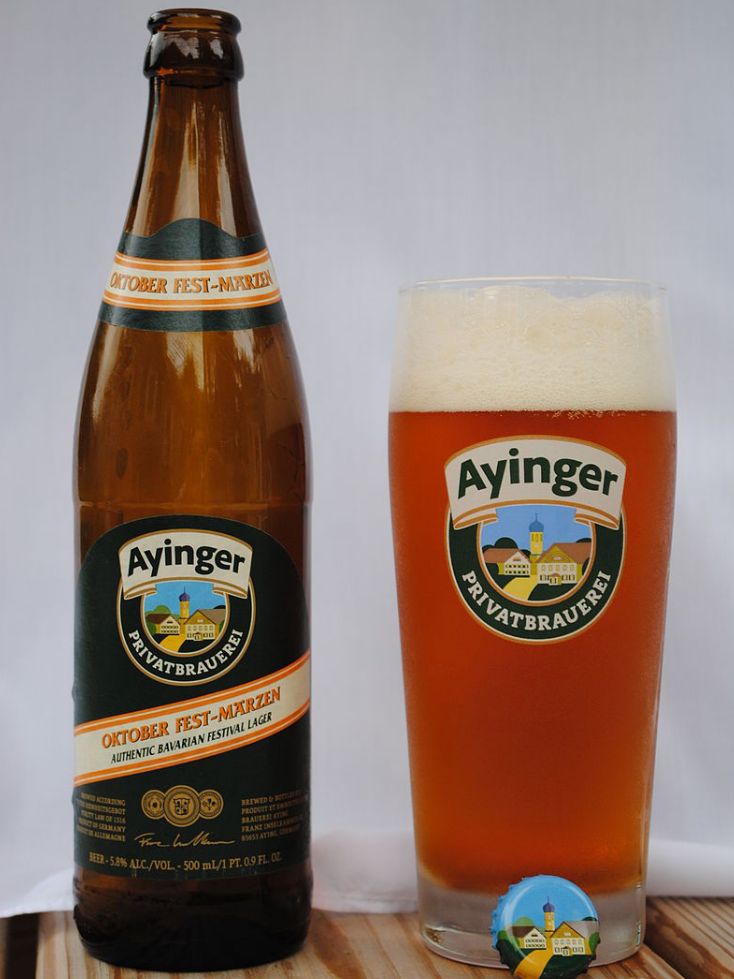

OKTOBERFEST BIER / MÄRZEN First of all, it should be noted that there is no real difference between Oktoberfest bier and Märzen — if you see either one, for all intents and purposes, you're in for the same range of flavors, colors, and aromas. So what are Oktoberfest biers/Märzen? They're beers served during Oktoberfest, the largest beer festival in the world held every year in Germany between late September and early October. This means that what ties these beers together is a time of year (Märzen means "March" in German) rather than a specific set of brewing and flavor profile criteria, although nearly every single Oktoberfest bier is a lager. Also, there are plenty of Oktoberfest biers that are made year round (just to make things a bit more confusing...).

One example of an Oktoberfest bier/Märzen. Image: Wikimedia / Ramseyjacob

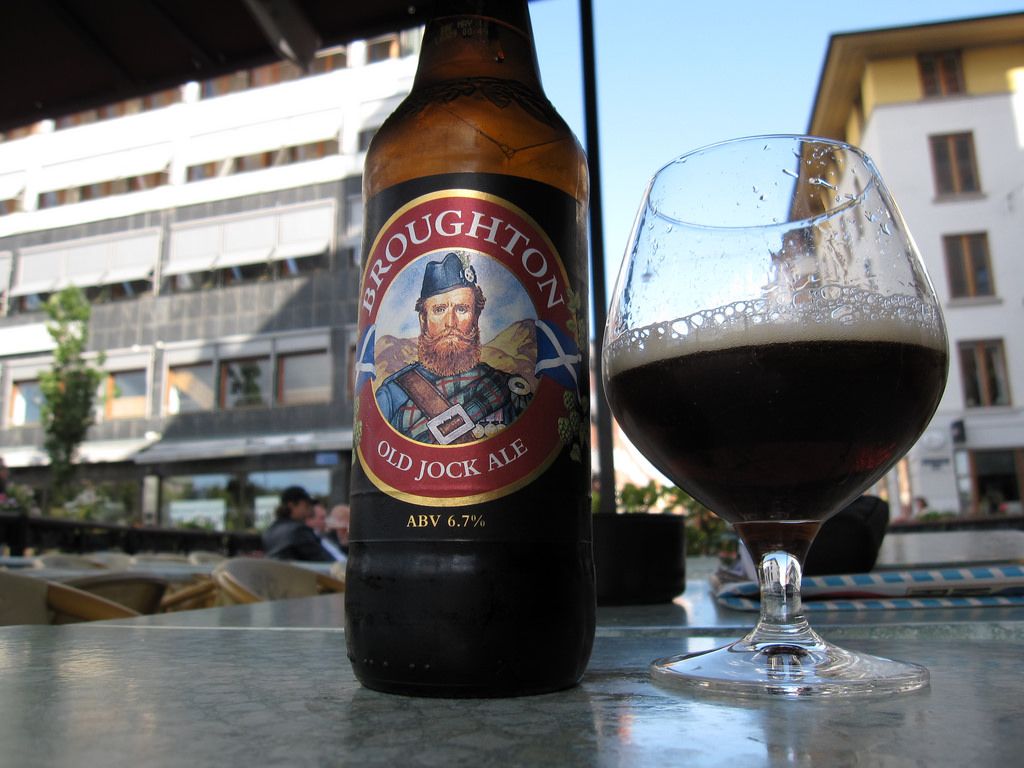

Flavor-wise, you can expect Oktoberfest biers to be crisp, medium-bodied lagerbiers (lagers) with spicy malt flavors. They're also toasty, moderately sweet, and have an average ABV of around 5-6%. Color-wise, they reflect fall with a palette ranging from amber-orange to reddish-tinged copper. As a technical aside, not all Oktoberfest biers aren't necessarily Märzens — the only real criteria for a beer to be officially recognized as a German Oktoberfest bier is that it needs to follow the Reinheitsgebot (the "German Beer Purity Laws" that regulate beer), be brewed within the Munich city limits, and be served at Munich's Oktoberfest. OLD ALE Old ale is a term applied to dark, malty ales made in England that are usually above 5% ABV. The term is also applied to Australian dark ales of any ABV. Despite its name, the category of old ales isn't only comprised of ales that are literally old, they're simply beers made to emulate beer from the 18th century, which was cellared in oak barrels for extended periods of time. Character- and flavor-wise, old ales offer a malt-heavy taste, thick mouthfeel, and a subtle, lingering sweetness. They also have hints of fruit, caramel, molasses, and toffee. Older old ales are sometimes described as reminiscent of port or sherry. OUD BRUIN Oud Bruin ("Old Brown" in Dutch) or Flanders Brown is a style of ale made in the Flemish region of Belgium. The name refers to the long aging process, which can take up to a year, required to make the beer. Oud Bruin's extended aging period allows for residual bacteria and yeast from the fermentation process to generate a characteristic sour flavor. Oud Bruins tend to be medium bodied, slightly malty, and completely lacking in hops bitterness. Color-wise, they're usually a reddish-brown.

One example of an Oud Bruin beer. Image: Wikimedia / Dirk Van Esbroeck

PALE ALE Pale ales are ales made with a mostly pale malt mash bill. Most notably, they are often credited with inspiring a beer renaissance in the U.S. roughly three decades ago. Although pale ales go back much further in time, first appearing in the early 18th century. There are two types of pale ales, English and American. British pale ales generally made with nuttier, more robust malt, while American pale ales are usually softer and more crisp. The hops flavor also differs, with the English hops being more refined and floral and the American hops being a combination of bold-citrus and pine flavors. Both types of pale ale are generally amber-gold with aromas of fresh citrus and fruits, and are around 4.2-6% ABV. PILSNER/PILS Pilsner is a type of pale lager that originated in the Czech Republic when it was a part of the Austrian Empire — it's named after the Bohemian city of Pilsen, where it was first produced in the mid-19th century. Pilsners break down into three different types: German-style Pilsner — relatively sweet in taste as it can be made from other malts besides barley. Lighter in body and color than Czech pilsners, as well as drier and crisper. The style, originated by the Czechs, was adapted by Germany in the 19th century.

One example of a German-style Pilsner. Image: Wikimedia / Felix Stember

Czech-style Pilsner — generally has a stronger hops bitterness and earthy tones. Light straw to golden in color. American-style Pilsner — American pilsners usually have a relatively high malt flavor relative to the Europeans' styles. They also tend to be higher in ABV at around 6.5-9%. PORTER Porter is a British, dark style beer that's usually brown or nearly pitch black in color. Flavor-wise, you should expect notes of roasted barley or malt, fruity esters, with a lack of the bitter notes offered by a stout. Aromas include roasted grains, chocolate, and toffee, and there are often undertones of coffee or licorice. Although you'll hear people treat porters as a separate category from ales and lagers, porters are technically ales.

One example of a Porter beer. Image: Flickr / edwin

RED ALE / AMERICAN AMBER American amber is named after its golden to amber color and is an Americanized version of English pale ale. The color of the beer comes from the use of caramel and crystal malt additives, which are roasted. American amber also sets itself apart from European pale ales by using American hops and grains. The flavor profile is a blend of strong malty flavors like chocolate, caramel, and toasty malts. There is still a strong bitterness present, however, and ranges from medium to high. Aromas of caramel, chocolate, and nuttiness are often present. The ABV tends to range between 4.5 and 6.5%. ROGGENBIER Roggenbier, which literally translates from German to "rye beer," usually consists of 50% malted rye, although some even have 65% or more. This style is usually cloudy, highly carbonated, unfiltered, and foamy. Expect a range of grainy, spicy flavors, with low levels of bitterness and tones of tart citrus, vanilla, or bubblegum. Roggenbiers are often referred to as naturtrüb, which means "naturally turbid" in German. Turbid is a term used to describe a beer's cloudiness or opacity. ABVs tend to range from 4.5 to 6%.

One example of a Roggenbier. Image: Wikimedia / JoergWoelk

SAISON Saison is a speciality beer from the Belgian province of Hainut. Saisons are especially high in carbonation thanks to secondary fermentation taking place in the bottle. Flavor-wise, expect soft malt, and various spicy and fruity flavors. There's also a mild hoppy bitterness present, although it doesn't overwhelm the spiciness of the beer. ABVs usually range from 5 to 8.5%. SCOTCH ALE There are two types of Scottish ales: Scottish Ales and Scotch Ales — yes, that's confusing, but blame the Scotts not us. Here are little descriptions of each one: Scottish Ales — Scottish Ales tend to be light, though they still have plenty of flavor and aroma. They tend to have a relatively low alcohol content, ranging from 2.5 to 5% ABV, and are thusly very sessionable beers.

One example of a Scottish ale. Image: Flickr / Bernt Rostad

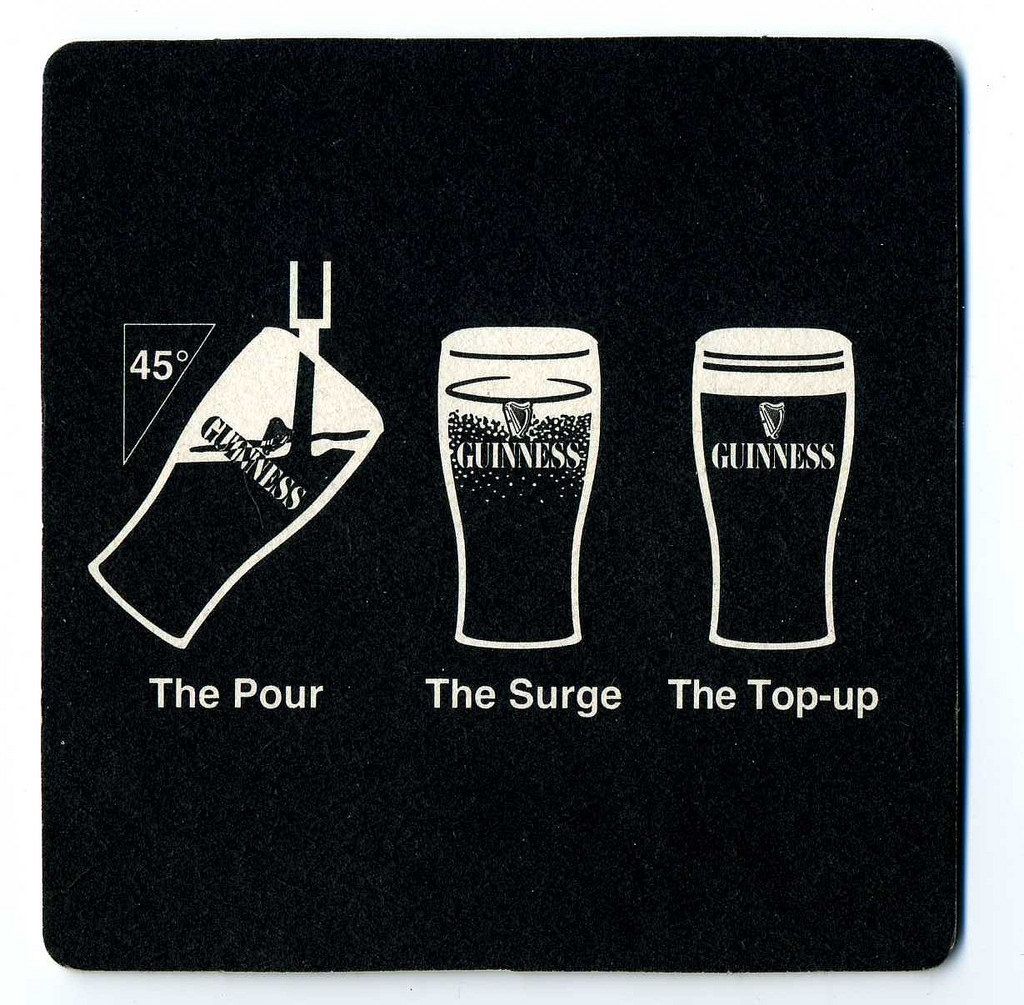

Scotch Ales — In contrast, Scotch Ales tend to be big, meaty beers. The ingredients used for both beers are usually just about the same, although Scotch Ales have more of said ingredients thrown in the mash. Scotch Ales often have a complex set of flavor notes ranging from roasted malt to earthiness to plums and dried fruit. Scotch Ales' ABV range between 6.5 and 10%. STOUT Stout is a dark beer that was originally a stronger ABV spinoff of the Porter style. Technically, stout is a type of porter, and was even originally referred to as a "stout porter." Due to this close intermingling of origin, it's often hard to differentiate porters from stouts. Even stouts defining characteristic, being stronger in ABV than porters, doesn't really hold up anymore. Some porters are weaker than Stouts and vice versa. Here are four stout categories you're likely to come across: Dry Irish Stout — Dry Irish Stouts are what you probably think of when you think of a classic stout — this category includes famous beers like Guinness, Murphy's and Beamish. Expect a dark color, an ABV of around 3.5 to 5.5% and a medium body. Russian Imperial Stout — Russian Imperial Stouts are incredibly hoppy and have a high ABV of around 8 to 11%. They generally have aromas reminiscent of chocolate, cocoa, and roasted barley. Flavor-wise, they have a grainy sharpness, moderate sourness, and a high hoppy bitterness.

One example of a Russian Imperial Stout. Image: Flickr / Bernt Rostad

Oatmeal Stout — Oatmeal stouts are a relatively sweet stout with an ABV ranging from 4.2 to 5.9%. This type of stout was originally brewed by the British, and after a period of decline was revived by Yorkshire brewer Samuel Smith in the 1980s. Oatmeal stouts derive their unique flavor profile from the use of oats in place of roasted malt, which enhances mouthfeel and body. They're usually highly flavorful with a hint of sweetness and a velvety texture. There are sweet and salty aromas, with hints of nutty oatmeal and fruit. Overall very earthy, nutty, and chocolatey. Sweet (or Milk) Stout — Sweet stouts usually have more unfermented sugars and residual dextrin than other stouts, which give them their uniquely sweet flavor profile. Sweet stouts range in ABV from 4 to 6%. Milk stouts are a variation on the sweet stout style, and usually contain lactose and milk sugars. (Be prepared to open a few windows after drinking a few of these bad boys.)

One example of a milk stout. Image: Flickr / Club Soda Guide

SCHWARZBIER Schwarzbier (which literally translates into English as "dark beer") is a dark lager made in Germany. Made using a lager fermentation method, schwarzbiers usually have an ABV ranging from 4.1 to 5% and have a bitter yet slightly sweet flavor profile marked by chocolate and coffee notes. The dark color comes from the use of roasted malt in the mash. WITBIER Witbier (which translates from Dutch to "White Beer") is an ale produced mainly in Belgium that's pale and cloudy in appearance thanks to the use of wheat, and occasionally oats, in the mash. Witbier is always spiced, usually with orange peels and coriander, although there's often other spice and herb flavors in the background. There's also a crisp tang that comes from the use of wheat and the high levels of carbonation from the beer continuing to ferment in the bottle. ABV ranges from 4.5 to 5.5%.

One example of a witbier. Image: Flickr / Josep Trepat Font

VIENNA LAGER Vienna lager, which is named after its city of origin, is made using a three step decoction boiling process. (This means that about a third of the mash used to make the beer was removed from the mash tun, placed into another pot to be heated to conversion temperature, boiled, and then returned to the main mash.) Vienna lagers usually range in color from a pale amber to a more reddish hue. Flavor-wise, the beer has a crisp, toasty flavor, with residual caramel sweetness, and often tastes similar to German Märzen. ABV ranges from 4.7 to 5.5%. WEISSBIER Weissbier is a German wheat beer that typically mixes 50% wheat and 50% barley in the mash. Usually unfiltered, this ale is yeasty, cloudy, and slightly white in appearance. Flavor-wise, most weissbiers are tart, and sometimes intensely sour. The intense tart flavor comes from the use of lactic acid bacteria in the brewing process. There are also often notes of vanilla, cloves, banana, or bubblegum. Aromas include prominent phenol and fruity ester notes. ABV ranges from 4.3 to 5.6%.

One example of a weissbier. Image: Flickr / Jeremy T. Hetzel

SPECIALTY BEERS

For all intents and purposes, just think of speciality beers as a category that works as an umbrella term for beers that don't fall neatly into any other category. Because of the nebulous boundaries of the category, expect flavors to vary greatly; what does generally tie these beers together are bold, experimental flavors and the use of unusual ingredients, fermentation agents, and malts. There are no established standards for appearance, aroma, or flavor for these beers. FRUIT BEER Fruit beers are those that are made with fruit or fruit extracts during any point in the brewing process. These beers' flavor profiles depend on whether the fruit seasonings have been used in the fermentation process or as an additive (which often comes in the form of an extract or juice); those that have fruits added during fermentation will have much more pungent fruit flavors. Expect fruity aromas for all types of fruit beers. Although fruit beers have gone in and out of fashion over the last few decades — with the latest revival coming thanks to the craft beer revolution — archaeological evidence points to the very first beers ever being brewed as probably containing fruit, including hawthorn fruit and/or grapes.

One example of a fruit beer. Image: Flickr / edwin

HERB AND SPICED BEER Herb and spiced beer can be either a lager or ale that has a flavor profile derived from vegetables, certain fruits, seeds, roots, or flowers. This type of specialty beer is usually low in hoppy bitterness, with a wide range in terms of mouthfeel, aroma, and appearance. The wide range comes from the varied use of spices and herbs used in the brewing process. HONEY BEER Honey beers are those that are (at least partially) fermented from a honey base. Honey beers also — massive surprise incoming!!! — have either subtle or overt tones of honey in their flavor profile. In general honey beers shouldn't taste like mead; they should just have honey flavors that supplement the rest of the flavor profile. Mead — Mead is a beer that's made with three ingredients: honey, water, and yeast. It can be either dry or earthy still or sparkling, and usually full-bodied. Unlike honey beer, you shouldn't expect any kind of complex flavor profile. Meads range widely in terms of ABV, from 3 to 20%. (All those fermentable sugars from the honey helps the beer to hit that especially high ABV mark.)

One example of mead. Image: Wikimedia / Matthewsmith959

Braggot — Braggot (also referred to as bragot, brakkatt, or brackett) is a form of mead that's made with both honey and barley malt. In order to be defined as a braggot, at least 30% of the malt has to be honey. The key difference between mead and braggot is that mead is made solely from honey while braggot is made from a combination of honey and barley. Braggot ABVs usually range from 6 to 13%. RYE BEER Rye beers are those that have been brewed with at least a portion of malted rye, which is substituted in for barley malt. They are also usually fermented with unusual organic ingredients like rice, corn, and wheat. Flavor-wise, expect tones of toffee, cocoa, chocolate, caramel, and biscuit-like flavors. Hoppy bitterness is definitely present, although not overwhelmingly so. The addition of rye to the mash bill also generally adds a pumpernickel character to the flavor and finish. Rye beers have become popular in recent years thanks to craft brewers who focus on IPAs. SMOKED BEER Smoked beer is generally considered to be more of a characteristic than a style, although beers that have a distinctive smoke flavor thanks to malted barley can generally be lumped together, hence the category. The smoke flavor comes from the fact that the malt is dried over an open flame. The distinctive flavor of smoked beer can range from dense campfire to lightly smokey. Beers that often have a smokey character include German-style Märzen, German-style Bock, German-style Dunkel, and Vienna-Style lager.

One example of a smoked beer. Image: Wikimedia / Tom Harpel

VEGETABLE BEER Like fruit beers, vegetable beers are those that have been brewed with vegetables. Vegetable beers are often made with root vegetables, tomatoes, carrots, mushrooms, squash, cucumbers, or pumpkin. Pumpkin ales are probably the most prolific type of vegetable beer. WILD BEER Wild beers are those that have been fermented with the Brettanomyces yeast strain as opposed to the far more popular Saccharomyces strain that's often used for both ales and lagers throughout the world. Wild beers also use "wild yeasts," which are those that aren't intentionally added when the yeast is pitched (thrown into the mash tun). Basically, when you think of wild beer, think of beer that's brewed, at least in part, with non-traditional yeast. Although wild beers range in flavor and/or color, expect a "funky" sour flavor as well as notes of Band-Aid, barnyard, and mild fruits such as apricot. Wild beers are also generally relatively low in terms of ABV, which makes them sessionable.

One example of a sour beer. Image: Wikimedia / Bernt Rostad

SOUR BEER Sour beer is, like smoked beer, more of a term describing the character of a beer rather than a strict beer category. Wild beers, lambics, Flanders, Gose, and Berliner Weiss can all be considered sour beers, and those are just a few examples. Sour beers are made with wild bacteria and yeasts — including lactobacillus and pediococcus — which result in their characteristic sour flavor. Flavor-wise, expect sour beers to be tart, funky, earthy, and of course, sour. As a side note, you may hear people use the terms wild beer and sour beer interchangeably, although they really shouldn't be as not all wild beers are sour beers and not all sour beers are wild beers. Wild beers are always made using wild yeast and other types of undomesticated microflora, while sour beers are categorized purely by their sour, acidic flavor. WOOD-AGED BEER AND BARREL-AGED BEER (THEY ARE NOT THE SAME!) Although you'll here the terms "wood-aged beer" and "barrel-aged beer" used interchangeably, they are not really the same. Barrel-aged beers are those that have been aged in barrels, while wood-aged beers are those that involve wood at some point in the brewing process, often during the fermentation step when wood chips (or even wood planks) are added. Flavor-wise, wood-aged beers tend to have notes of hickory chips, barbecue, toasted oak, vanilla, chocolate, coffee, and even a slight bourbon flavor.

One example of a barrel-aged beer. Image: Flickr / Peter Anderson

101 COMMON BEER TERMS TO LOOK OUT FOR

Following are 101 terms you're likely to come across as you learn more about beer. You'll want to commit these terms to memory and use them liberally if you want to be considered a true beer snob.FLAVOR TERMS

Big — "Big" describes a beer that's very flavorful and/or high in alcohol content. Crisp — Crisp means that the beer is highly carbonated or effervescent (fizzy). Crisp beers are also often on the drier side. Cloying — A beer that is overly sweet. Hoppy — Hoppy is basically a description of bitterness. A beer that's very hoppy is very bitter while a beer that isn't hoppy isn't as bitter. Malty — Malty generally describes a combination of flavors. These flavors include: sweet, nutty, toasty, caramel, coffee, and fruits like raisins. Roasted — Roasted is a term that often refers to a roasted barley flavor, which is coffee-like. This flavor is often associated with stouts. Smoky — Smoky is exactly what it sounds like; tasting like smoke. This taste generally comes from malt being dried over an open fire. Spicy — Spicy is exactly what it sounds like; having spicy flavors. Spice flavors include flavors like chili peppers, black and green peppers, cumin, and peppercorns. Tart — Tart is self-explanatory — it means that the beer is tart. Funky — Funky is a very nebulous term and some beer connoisseurs don't even bother to use it. Generally it's thought of smelling and tasting like horse sweat, Band-Aids, barnyard, or even funky cheeses. Beers brewed with Brettanomyces yeast are generally considered to be quite funky. Acetaldehyde — Acetaldehyde smells and tastes like green apples. It's often described as "acetic cider." Astringent — Astringent describes a drying, puckering taste that can best be thought of what you'd experience when sucking on a teabag. This flavor causes the mouth to pucker. Bitter — Bitter is self explanatory. Bitterness most often comes from the hops included in the brewing process. Cabbagelike — This word is used to describe a beer that smells and tastes of cooked vegetables. Clovelike — Having a spicy characteristic that tastes like cloves. This flavor is often found in wheat beers. Fruity/Estery — Describing flavors and aromas that are fruity. These flavors are often derived from high-temperature fermentation and particular yeast strains. Yeasty — Yeasty is used to describe the taste of yeast. This flavor is often the result of yeast being leftover in the beer after the initial fermentation process. Sweet — Describes exactly what you think it would: sweet, sugary flavors. Sulfurlike — This term describes flavors that are reminiscent of rotten eggs or burnt matches. Hang — This is a term that describes a lingering harshness or bitterness on the tongue after a sip of beer. Solventlike — Solventlike describes flavors that are reminiscent of acetone or lacquer thinner. Salty — Tastes like table salt, often experienced on the side of the tongue. Sour/Acidic — Having a sour or acidic flavor. Often tastes like vinegar or lemon. Vinous — Reminiscent of wine. Medicinal Chemical or phenolic character; can be the result of wild yeast, contact with plastic, or sanitizer residue. Metallic — Flavor reminiscent of tin, blood, or coins. Can sometimes become a part of the flavor profile thanks to bottle caps. Musty — Reminiscent of mold; having a mildewy character. Grainy — Tastes like raw grain or cereal. These flavors are produced from grain husks and are often astringent. Diacetyl — A yellow-green liquid that's responsible for buttery flavors. Oxidized — Having a stale flavor reminiscent of wet cardboard, rotten pineapple, paper, or sherry. This flavor is due to the beer being oxygenated or exposed to high temperatures. Winy — Flavor reminiscent of sherry wine. Bacterial — General term describing off-flavors such as mold, must, wood, lactic acid, vinegar, or microbiological spoilage. Chlorophenolic — Describing a plastic-like aroma, derived from a chemical combination of organic compounds and chlorine.AROMA TERMS

Common flavor aromas: grainy, sweet, corn, graham crackers, biscuits, caramel, toast, coffee, espresso, alcohol, tobacco, pine, leather, gunpowder, fresh cut grass Common spice aromas: white pepper, cloves, anise, licorice, nutty, fatty, vanilla, earthy, horsey, bread-like, woody, musty, barnyard Hoppy — Having a hoppy smell, which translates to citrus, pine, earthy, and spicy aromas. Estery — Having aromas reminiscent of fruits or flowers. Light-Struck — Having a skunk-like smell due to overexposure to light. Dark Fruit Aromas: Aromas including those of raisins, currants, plums, dates, figs, blackberries, blueberries, prunes, etc. Light Fruit: Aromas including those of bananas, apricots, pineapples, pears, apples, peaches, nectarines, mangos, pears, etc. Citrus Notes: Aromas including those of lemons, limes, tangerines, oranges, grapefruits, clementines, orange peel, lemon zest, etc. Acidic-Type Aromas: Aromas reminiscent of vinegar, copper, cider, etc. Often smelling like champagne or chlorine.BEER APPEARANCE TERMS

Basic beer color terms (from lightest to darkest) — Pale straw, straw, pale gold, deep gold, pale amber, medium amber, deep amber, amber-brown, brown, deep brown, black Clear — A beer that doesn't have any visible particulate matter in it. Head This refers to foam on the top of the beer. The foam head should be thick, dense and tight for most beer styles. Some terms for describing a beers head are; persistent, rocky, fluffy, dissipating, lingering, frothy, tight, dense, smooth Turbid — Cloudy and opaque in appearance. This characteristic may also be described as hazy or cloudy. Beer head — The frothy foam on top of the beer produced from rising CO2 gas. Beers that are foamy have a lot of head. Lackluster — Describing a beer that's dull in appearance. Standard Reference Method — The Standard Reference Method (SRM) is the color system used by brewers to specify the color categories of finished beers, and malt.PRODUCTION PROCESS TERMS

Additive — Enzymes, preservatives, and antioxidants added to the brewing process to make things simpler or to extend the beer's shelf life. Adjunct — Fermentable materials used in place of traditional grains to create cheeper and/or lighter-bodied beers. Attenuation — The extent to which yeast converts fermentable sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Barley — Cereal grain used for the malt for brewing beer. Bung — The stopper placed into the hole in a keg through which the keg is emptied. The hole in the keg may also be referred to as a bung, or even a bunghole. (We're not kidding about "bunghole.") Brew Kettle — The vessel in which wort is boiled with hops. Brewhouse — The equipment required to make beer. Bottle-conditioning — Residual fermentation and maturation that happens in the bottle if all the yeast wasn't killed off during the brewing process. Bottle conditioning often creates complex aromas and flavors. Bottom-fermenting yeast — Yeasts that grow less rapidly than top-fermenting yeasts and tend to settle at the bottom of the fermentation tank (hence the term "bottom fermenting"). Bottom-fermenting yeasts are most often used for lagers, and work best at low temperatures. This yeast usually results in a crisp, clean, trademark lager taste. Cask — A barrel used for storing and/or aging beer. In regards to beer, they are often made of metal. Conditioning — Period of maturation intended to increase natural combination levels. Warm conditioning tends to develop complex flavors, cold conditioning tends to result in cleaner, rounder tastes. Conditioning Tank — The vessel beer is placed in after the primary fermentation process. Inside of this tank the beer matures, is clarified, and is naturally carbonated by remaining yeast. Conditioning tanks are also referred to as bright beer tanks, serving tanks, or secondary tanks. Cask-conditioning — Secondary fermentation and maturation that happens inside the cask. Dextrin — Unfermentable carbohydrates produced by enzymes in barley. Dextrin gives beer distinctive flavors, body, and mouthfeel. Dosage — The addition of yeast and/or sugar to a cask or bottle to aid secondary fermentation. Dry-hopping — The addition of dry hops to beer's fermentation or aging process to increase hop flavors and aromas. Heat Exchanger — A mechanical piece of brewery equipment used to quickly raise or lower the temperature of the wort. Hop back — A vessel used to strain out the petals from hop flowers. Also known as a "hop jack" in the U.S. Enzymes — Natural catalysts found in the grains used to make beer. When heated during the mashing step, these enzymes convert starches into fermentable sugars. Fining — A process that aids clarification by pulling out particles suspended in the brew. Filter — Filters, often made of diatomaceous earth (microscopic skeletal remains of marine animals), are used to pull out impurities from the brew. Keg — A container with a volume of 15.5 U.S. gallons; a half keg is 7.75 U.S. gallons and is often referred to as a "pony-keg." Regional specialty brewery — A brewery that produces more than 15,000 barrels of beer a year with the largest-selling product being a specialty beer. Lagering — Lagering refers to the process by which beers are matured for weeks to months at cold temperature to settle out residual yeast, develop carbonation, and clean clarify the beer's flavor profile. Lager in German literally translates to "warehouse," hence the term being used for the storage/maturation process. Length — The amount of wort brewed every time a particular brew house is operational. Liquor — Liquor is a brewer's term for the water used in the brewing process (e.g. during the mashing step). Maltose — Water soluble, fermentable sugars contained in malt. Malt Extract — Condensed wort that's been further processed into dried (powder) or liquid (syrup) sweeteners. It is often used by brewers in water and extract solutions to re-infuse wort with more fermentable sugars for the following fermentation process. Mash Tun — The tank in which grist is soaked in warm water. It is inside of the mash tun where the grains' starches are turned into fermentable sugars. Pasteurization — Pasteurization is the process of heating beer to kill off any harmful, living microbes without changing the chemistry — and most importantly, the flavor and character — of the beer. In general, the pasteurization process helps to stabilize and sterilize the beer. This process takes a fairly short period of time, ranging from 20 minutes to only 15 seconds. Pitch — To add yeast to the wort. Priming — Adding sugar to a beer's maturation stage in order to promote secondary fermentation. Sparge — "Sparging" means that a brewer is spraying grist with hot water in order to remove any and all soluble sugars. This step takes place at the end of the mashing process. Tun — Any vessel used in the brewing process. Americans often refer to tuns as tubs. Top-fermenting yeast — Top-fermenting yeasts are those that work at warmer temperatures and are able to handle higher alcohol concentrations without being killed off. (As opposed to bottom-fermenting yeasts that require cooler temperatures and lower alcohol levels.) This is the kind of yeast that is most often used for brewing ales, and because it's unable to ferment some sugars, often results in a fruitier, sweeter beer. Original Gravity (OG) — Original gravity, in regards to the brewing process, is a measure of how dense a wort (the sugary water that's produced from the mashing step) is relative to the density of water. This is an important measurement because it's a good indicator of how much sugar is in the wort; the more sugar, the higher the density. This is also an important measurement for making sure that all the beer produced is consistent in terms of alcohol content and character. Note that original gravity (OG) is interchangeable with specific gravity (SG). Final specific gravity/terminal gravity — Final specific gravity, also referred to as "terminal gravity," is the specific gravity of the beer once fermentation is complete.CHARACTER TERMS