The Ultimate Sake Guide: Everything You Need to Know!

WELCOME TO SAKE

No home bar would be complete without a bottle of sake, the Japanese spirit that can turn any random Friday night of sashimi and ramen takeout into a full-blown (imaginary) trip to Tokyo. Served chilled, warm, or room temperature, neat, as a bomb shot, or in a cocktail, this versatile, moderate ABV alcohol will doubtlessly serve you well on your mission of becoming a sensei of the drink-making arts. https://giphy.com/embed/xUPGcsiNHoFdtXWG1q But before becoming a sake sensei specifically, you must first learn as much as you (realistically) can about this spirit so that you're well armed with enough knowledge to strike down any challenges to your claim of being a true connoisseur. With that need in mind — as well as the need to be able to buy the right sake and mix it well in cocktails — we present to you here the Ultimate Sake Guide. Once you've made your way through this breakdown of sake and learned about where it comes from, how it's made, what forms it comes in, and how to drink it properly, we promise you'll be able to impress anybody at your next house party or outing at a bar with your extensive knowledge — even if you're chatting up a tōji . (And, yes, you will learn what a toji is.) https://giphy.com/embed/2NOSHIyDKPR5eWHAT IS SAKE

Yes, you've probably done some sake bombs with your friends at a ramen or sushi restaurant, and yes, you may have even knocked back a few shots of sake neat because some anime or a Kill Bill movie put you in the mood, but aside from a few novelty interactions with Japan's signature spirit, have you ever sat down to learn about what it actually is? Don't fret if you haven't Tipsy-san, because even though sake can get pretty nuanced in some areas, it's basically a fermented rice wine. Although there are aficionados out there who would argue that it's more of a beer, or maybe even a combination of both — we'll go deeper into this in the sections below. What is a "fermented rice wine" you're now asking yourself? Well, that's basically an alcoholic liquid that's been made by taking rice and fermenting it. (Fermentation is the process by which yeast turns fermentable sugars into ethanol and a few other byproducts.) But this is a gross oversimplification of the sake-making process, and the process is actually not simply about fermenting rice wine, it's about "parallel fermentation" — which, again, we'll get more into below. https://giphy.com/embed/Wa43p62jUcXAs In regards to where sake comes from, here are the soundbites you'll need to know if somebody corners you at a little friend gathering or a big drunken Samurai competition (that's probably not a thing, but if it is, you'll be able to show off your sake knowledge there too): The exact origin of sake is uncertain, but the spirit's wiki notes that it was probably in Japan during the Nara Period, roughly 710-794AD. During the following Heian Period, which started when the Nara Period ended, sake became a part of court festivals, religious ceremonies, and drinking games. By the 10th century, shrines and temples began to brew sake, and it was there that it would be predominately produced for the next 500 years. In the 20th century, things changed dramatically for sake, and not necessarily for the better. World War II forced the Japanese government to clamp down on sake brewing due to rice shortages, which resulted in brewers adding pure alcohol and glucose (sugar) to their rice mashes (the alcoholic liquid made from fermenting rice). This process of diluting rice mash with added alcohol and glucose became prevalent and continues on today. Which may be part of the reason that, since the 1960s, sake has been losing ground in its home country to the likes of beer, wine, whiskey, and other spirits....

American and Japanese representatives break open ceremonial casks of sake. Image: Wikimedia / United States Navy

Although these are the brief sake strokes you'll need to know, we'll get more into everything discussed here in the sections below. So without further ado, here is your full rundown of sake, beginning with a more in-depth history! But first, an important note: In Japanese "sake" doesn't just mean "sake." Instead, it is a reference to all types of alcohol. So if you happen to be speaking to somebody from Japan (in any language) make sure you clarify whether they're talking about this type of alcohol specifically or alcohol in general.A (VERY) BRIEF SAKE HISTORY

Now that you know what sake is — or at least have a very general idea of what it is — it's time to take a slightly more in-depth look at where it came from and how it grew and matured into the spirit it is today. As always, because there's so much information to cover, we'll be boiling everything down to just a handful of highlights.SAKE IS BORN IN JAPAN IN THE 8TH CENTURY (PROBABLY)

As mentioned in the above section, the most likely origin of sake is in 8th century (Nara Period) Japan. It's hard to say exactly where in the country it happened, but in terms of the how, it was basically a matter of sake evolution. Even before the creation of sake as we know it today, a slightly different type of sake was being produced; one where people infused rice with the right enzymes to turn its carbohydrates into fermentable sugars by chewing on it. Once the rice's carbohydrates had been turned into fermentable sugars by people's saliva, the rice would spat into receptacles. Those receptacles would then be dumped into tanks, to which yeast would be added to process the sugars into alcohol, as well as a few other byproducts like CO2. This changed in the 8th century when instead of using saliva to convert the rice's sugars into carbohydrates, brewers began using a mold, Aspergillus oryzae, also known as koji. From then on, until today, that process became the way the vast majority of sake was (and is) created.SAKE BECOMES A POPULAR SPIRIT IN JAPAN

After sake reached its final form in the 8th century, it experienced a massive growth in popularity over the next 1,200 years. Temples and shrines began producing it over the next 500 years, and by the 19th century it had become so popular that on one occasion 30,000 breweries were launched in a single year. Unfortunately for the sake industry, this number dwindled to 8,000 due to government taxation.

A sugitama, which is a globe of cedar leaves that's hung outside of sake breweries when new sake is being brewed. Image: Wikimedia / さかおり

SAKE IN THE 20TH CENTURY

The 20th century started off really well for sake, with the Japanese government's support going so far as to create a sake research institute and a sake tasting competition. But World War II interrupted the sake industry just as it did all others, and due to rice shortages and subsequent government mandates on use, sake was forced to change into something that was fundamentally different from what it once was. To deal with the rice shortages, sake brewers began supplementing their fermented rice mash with added alcohol and sugar. And while it's debatable whether or not this method of production constitutes a genuine sake, there's no doubt that this became the predominate method for making sake, especially when it comes to cheap sake. Just a few decades later, in the 1960s, sake market share started shrinking. It began to take the runner-up position to wine, beer, and spirits like whiskey. Since then, sake has seen its sales dwindle, with 2016 shipment levels falling back down to those of 1955.SAKE IN THE U.S.

Sake production began in the early 20th century in the U.S. in the great state of Hawaii, which actually wasn't a state in 1908 when the Honolulu Sake Brewery first made sake — although it would eventually become a U.S. state. The brewery was meant to serve first-generation Japanese immigrants, but after World War II things began to look very grim for the Honolulu Sake Brewery thanks to the aforementioned rice shortage. The Hawaiian sake brewery was saved, however, when brewmaster Takao Nihei (a native Japanese man) — deemed the "father" of sake production in the U.S — decided to step in and keep it from going under. Soon after the rescue of the Honolulu Sake Brewery, other sake companies began popping up in the U.S. looking to grow their market share in the alcohol industry in the U.S.

An American-made brand of sake. Image: Wikimedia / PPGMD

HOW SAKE IS MADE

Now that we know what sake is and where it came from, it's time to look at how it's actually made. And because traditional sake is made from fermented rice without any additives, we'll stick to describing the basic process without getting hung up on production caveats that may be popular, but are nonetheless unnecessary. Side note — what is a toji? If you really wanted to learn everything there is to know about brewing sake, you'd want to talk with a toji, which is basically a sake brew master. Tojis are highly respected in Japan, and are as revered as musicians or painters. And although the profession of toji is in danger of becoming obsolete, there are still some Japanese people choosing to study the craft in universities or even as a kind of graduate program after earning veteran status as brewery workers.RICE

The first thing that's required to make sake is rice. But not just any rice: only saka mai or "sake rice" will do, as its grains are larger and stronger than other types and also contain less lipids and proteins. This saka mai will then be milled in order to have its grains' outer layers removed leaving behind their starchy cores. This process is known as "polishing." Note that how much rice grains are milled will change which category a particular sake belongs to, but we'll go further into that in the section below.

A jar of polished white rice. Image: Flickr / Marco Verch

WASHING AND SOAKING

After the rice has been milled it's then time to wash and soak it. Washing the rice grains (which are held in porous sacks at this point) will help to remove the dust made of residual protein particles and other unwanted lipids and proteins leftover from the milling process, which could ultimately negatively affect the flavor of the sake. After the grains have been washed, they're then soaked in order to infuse them with water that will be steamed off in the next step.STEAMING

Once the rice has been washed and soaked, it's then time to steam it. Although for sake production the rice isn't steamed as it normally would be for regular rice that's just made for eating. Instead of being mixed with water and brought to a boil, rice for sake is placed over a steaming vat (traditionally known as a koshiki) where it has piping hot steam passed through it. https://giphy.com/embed/l0MYvKMxYkX81J9Ty As far as why the sake rice is steamed, that's a matter of cooking the rice in such a way that it's not made too crunchy or too sticky; either of those characteristics would diminish the effect that the koji (discussed in the next step) has on the rice.KOJI MAKING (SEIGIKU)

Once the sake rice has been milled, soaked, washed, and steamed, it's then time to get a little funky and add some koji (Aspergillus oryzae), which is a mold that will turn the rice's carbohydrates into fermentable sugars thanks to its containing the right enzymes to catalyze that process. (Recall that this used to be done by people just chewing the rice and getting their saliva all over it.) In terms of how the mold is actually added, that's simply a matter of laying out the rice and then sprinkling it on. This process is also known as Saccharification.

Koji (Aspergillus oryzae) growing on rice. Image: Wikimedia / Forrest O.

THE YEAST STARTER / MAKING THE MAIN MASH (MOROMI)

Once the koji has been added to the rice, the process of fermentation can begin. Although this is where things get pretty tricky and intricate, as, despite it being called "fermented rice wine," sake is actually made in a unique way that calls for "multiple parallel fermentation." As you may guess, multiple parallel fermentation means that the mix that goes into the fermentation tank simultaneously undergoes the process of saccharification and fermentation. This begins with what is known as a "yeast starter" or Moto, which is basically just a combination of sake rice, sake rice combined with koji, water, yeast, and, in most cases, lactic acid.

Vat used for brewing sake. Image: Flickr / tokyofoodcast

Once this moto combination has been created inside of a fermentation tank, more of each ingredient is added in stages. There are a lot of nuances in terms of how the ingredients are added — in terms of quantity and when in the fermentation process they're added — but for all intents and purposes, you just need to know that when it comes to sake, the fermentation process happens in conjunction with the saccharification process. This differs from, say, beer, as beer first has its starches turned into sugars, and is then exposed to yeast to be fermented.PRESSING THE MASH (JOSO)

Once the main mash has been made, and all of the starches have been turned into fermentable sugars and all of the fermentable sugars have been turned into alcohol (and other byproducts), it's then time to press the mash. And yes, you can probably guess exactly what this step entails. Pressing. The. Mash. This is an essential step because even though the fermentation tank is full of boozy liquid at this point, said boozy liquid is still tainted with undissolved rice and koji. In fact, the mash has so much solid material in it at this point that it's actually mushy. In order to transform this mushy mash into pure liquid sake, it's poured into porous bags again, which are then placed in a "fune," which is a traditional press used for making sake as well as other products. Once the mushy mash bags have been placed in the fune, the boozy liquid is pressed out of the bags, leaving all — or at least most — of the solid material behind.FILTERING THE SAKE MASH (ROKA)

Despite the fact that most of the solid materials are pressed out of the sake during the previous stage, the boozy liquid still needs to be filtered to make sure it's fully cleared of all those particles drinkers would not want to taste while knocking back their sake. This filtration process uses a charcoal filter that inevitably changes the color and flavor profile of the sake, therefore greatly impacting the final product.PASTEURIZATION

After the sake has been filtered, it's then pasteurized by being passed through a pipe immersed in super-hot water. This increase in temperature the sake experiences as it passes through the heated pipe kills off bacteria and also deactivates enzymes that would have a negative effect on its flavor profile. Sake that isn't pasteurized is known as namazake, which literally translates to "fresh sake." Namazake tends to keep a certain freshness and flavor that pasteurized sake doesn't, although it must always be refrigerated in order to ensure that the aforementioned enzymes don't propagate and make the sake go bad.AGING THE SAKE / DILUTION / BOTTLING

After (or even before) the sake has been pasteurized, brewers have the opportunity to age it if they'd like to. This aging process happens in steel tanks and/or wooden barrels, and can last anywhere from months to years, although any kind of significant aging process is extremely rare. This aging obviously greatly changes a particular sake's flavor profile, especially if it's aged in wooden barrels; although on average aged sake is usually only rested for about six months before being bottled.

A wall of sake casks. Image: Flickr / Mark Gunn

After the (very optional) aging step, the sake is then usually diluted to drop its ABV percentage from somewhere around 20% to 16% and is then bottled and shipped off for consumption!THE DIFFERENT CATEGORIES/TYPES OF SAKE

We're getting closer and closer to the point at which we can actually start drinking some dang sake, but first we need to learn another piece of critical information — all the different types of sake. And folks let us tell you, there are a lot of different sakes. So let's go ahead and break them all down, shall we?

Various types of sake. Image: Flickr / John Seb Barber

Side note: The spelling for the different types of sake varies (with spaces, hyphens, etc.) so keep in mind that you may see different spellings for these types when you're actually looking at bottles on shelves. Double side note: Most sake categories are heavily dependent on how much the sake rice has been polished (milled down), as well as what percentage of the rice used is koji rice. But because those factors are fairly trivial for normal consumers, we're just going to focus on the qualitative differences between the sakes here.Junmai

Junmai is Japanese for "pure rice," which is an important distinction in the world of sake, where there are many non-pure rice sakes that aren't considered to be as legit as rice-only. As the purest form of sake, junmai is only allowed to be made with rice, water, yeast, and koji. It isn't allowed to have any added sugar or alcohol from other sources. If a sake label doesn't specifically say junmai, then you can bet on it containing added alcohol and/or sugar from other sources aside from rice. Despite junmai's claim to being the true OG sake, other sake types aren't necessarily inferior — so don't be too hasty in putting a bottle of sake back on the shelf just 'cause it isn't junmai.Honjozo

Honjozo is sake that uses rice grains that have been polished down to at least 70 percent during the milling process. This means that roughly 30% of the grains' exterior has been shaved off during milling. By definition, honjozo contains some amount of distilled brewers' alcohol that's used to smooth out the sake's flavor and aroma. Taste wise, honjozo sake is often thought of us light, easy to drink, and able to be enjoyed either warm or chilled.Ginjo and Junmai Ginjo

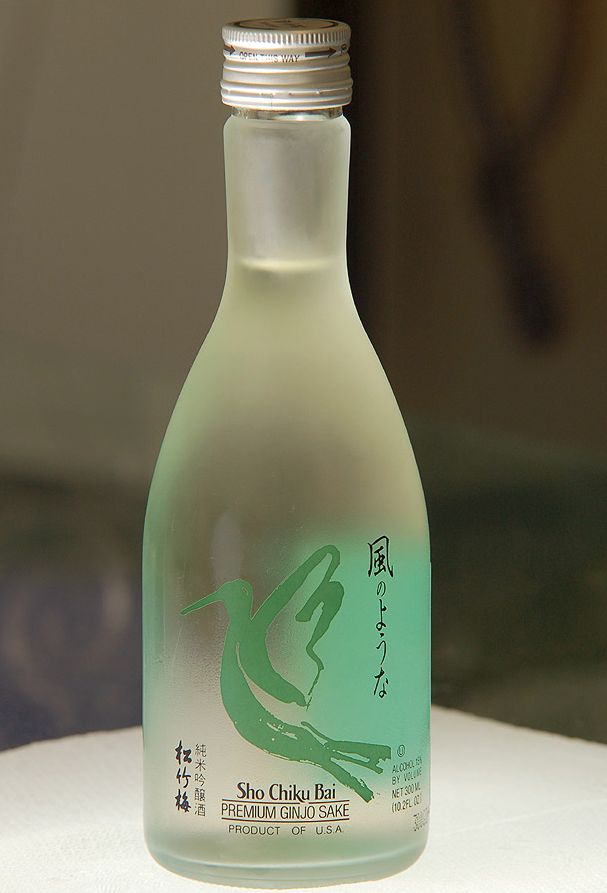

Ginjo is premium sake that's made from rice milled to at least 60%. (Again, that means that during the milling process, 40% of the rice grains' exteriors have been removed.) On top of using rice milled down to at least 60%, ginjo is also brewed using special yeast as well as special fermentation processes. The resulting sake is often fruity, light, and especially aromatic. It's also often served neat and chilled. Junmai ginjo is ginjo that, like junmai, is made purely with fermented rice with zero additive alcohols or sugars.

A bottle of junmai ginjo. Image: Flickr / Lou Stejskal

Futsushu

Futsushu, which is sometimes referred to as table sake, is sake that uses minimally polished rice (with the grains being milled down to somewhere between 70 and 93%) and is generally seen as the most inferior out of all the sake options. On top of having the least pleasant flavor profile, futsushu also has a reputation for giving people terrible hangovers....Shiboritate

Shiboritate is sake that undergoes no aging and is simply bottled and shipped right after the sake mash is pressed and filtered. In general, shiboritate's flavor profile is surprisingly fruity, and is sometimes even likened to white wine in taste.Seishu

Seishu is the legal term in Japan for sake that has had all of its solids strained out, leaving only a perfectly clear liquid. This means that sakes that have not been "properly" filtered, such as nigorizake, are not, by Japanese legal standards, technically sake. Although there is a way for nigorizake to achieve seishu status by being strained and having all of its cloudiness removed.Nigori

Nigori is sake that has only been coarsely filtered, allowing it to retain small bits of rice floating around inside of it. This retention of solid particles gives nigori a cloudy white appearance, as well as a silky smooth texture. In fact, some nigori sakes retain so much solid material that they can even feel thick and chunky in the mouth. Oddly enough, nigori seems to be far more popular outside of its home country rather than in it.

A glass of nigori. Image: Wikimedia / Marshall Astor

Jizake

Jizake isn't so much a category of sake as it is a generic term for "local sake." In other words, if you were to go to particular region of Japan and ask for their jizake, they would hook you up with the sake that's brewed in that particular region. Because jizake is regional, it's usually fresh and reasonably priced.Genshu

Genshu is sake that hasn't been diluted with water, which means it maintains an ABV of somewhere between 18 and 20%.Muroka

Muroka is sake that hasn't been carbon filtered. Despite the fact that muroka isn't carbon filtered, it's still pressed and strained to the point that dead yeast and other solids are removed. This means that muroka isn't cloudy like nigori, but still has stronger flavors than filtered sakes.Nigorizake

Nigorizake is sake that has only had its mash filtered through a loose mesh. As with nigori, nigorizake's lack of carbon filtration means that it takes on a white, cloudy appearance.Namazake

While most sake types are pasteurized twice — once after brewing and then again before shipping — namazake isn't pasteurized at all. This is why it must be kept refrigerated at all times. In regards to flavor, you can expect most namazakes to offer relatively fresh and fruity flavors along with a noticeably sweet aroma.

Some bottles of namazake. Image: Flickr / Shinsuke Ikegame

Koshu

Koshu is sake that has been made with the specific intention of being aged. Often times koshu will be aged for decades, which will cause it to turn yellow and acquire a honey flavor.Shiboritate

Shiboritate is sake that has been shipped without the usual six-month aging period. This means that shiboritate usually has a more acidic flavor relative to other sakes, as well as a greener coloration.Doburoku

Doburoku is home-brewed sake that is made by adding koji mold to water and steamed rice and letting the combination ferment. Doburoku is similar to nigorizake, although it's usually much chunkier. Also, this type of sake is technically illegal in Japan 'cause home brewing is against the law.Taruzake

Taruzake is sake that has been aged in wooden barrels made of Japanese cedar (sugi in Japanese).

A bottle of taruzake being poured. Image: Flickr / Adam Goldberg

Kuroshu

Kuroshu is sake made from totally unpolished rice, and is more like Chinese rice wine than classic sake.Teiseihaku-shu

Teiseihaku-shu is sake that is made with rice that hasn't been polished below 80% — meaning only 20% of the grains' outer layers have been removed. The goal of Teiseihaku-shu is to retain as much of the original rice flavoring as possible.SOME GREAT SAKE BRANDS TO TRY

Note that it may be difficult to get your hands on some of these bottles if you're in the U.S. Your best bet for getting quality sake and good sake advice is to go to a Japanese restaurant and ask them about their sake — where they get it and which brands they recommend. Other than Japanese restaurants, you can also try Japanese markets that sell liquor for some useful guidance. Also remember that when it comes to actually buying a bottle, the internet is hugely helpful. Here are some great bottles of sake from the categories above: Sohomare Junmai Ginjo (Junmai Ginjo, $55), Tenzan Shichida Junmai 75 sake (Junmai, $27), AMAWA Tokubetsu Junmai (Tokubetsu Junmai), SAWANO-HANA Hana-Gokoro (Honjozo), Funaguchi Kikusui Ichiban Shibori (Namazake), Hakutsuru Sayuri Sake (Nigori, $7), Jizake Tenzan Junmai Genshu (Genshu, $20), Sasaiwai Junmai Muroka (Muroka, $37), Shirayuki Sake Shiboritate (Shiboritate, $30), Suzuki Shuzoten Hideyoshi Flying Pegasus Koshu Daiginjo Sake (Koshu, $175).OTHER IMPORTANT LABEL NOTES

Aside from all the types listed above, it's also important that you know three more terms that you'll see pop up on sake bottle labels: Nihonshu-do, San-do, and Aminosan-do. Nihonshu-do is a measurement of the sweetness and dryness of a particular sake. Basically, if you see a Nihonshu-do measurement, it will be followed by number values between -4 and +10. Lower numbers indicate increased sweetness, higher numbers indicate increased dryness. San-do is an indicator of the acid concentration in a particular bottle of sake. Aminosan-do is a measurement of how much amino acid is in a particular bottle of sake. A higher aminosan-do number indicates the presence of more amino acids, and hence a richer flavor profile, while a lower number indicates less amino acids and a lighter flavor profile. Umami is a measurement of a sake's savory flavor and richness. Umami is often referred to as a "fifth flavor" because people believe it affects the tongue differently than salt, sweet, sour and bitter flavors. In terms of what it actually tastes like, it's usually described as a combination between spicy and salty.HOW TO DRINK SAKE

OK people, now that we know just about everything we need to to pass as sake pros at parties or bars, it's time to get to the really fun part: drinking the dang booze! But if you want to do it properly — respectfully! — then you'll want to have all of the following sake drinking tips crammed into your noggin before your next trip to the Land of the Rising Sun.SERVE IT IN A TOKKURI, SIP IT WARM FROM A CHOKO OR COLD FROM REISHU-HAI

First of all, when you're drinking sake, you're going to want to serve and sip it out of the proper drinkware. Luckily, you don't need to get too fancy, as you'll only really need a tokkuri and some choko. Well, also maybe some sakazuki and reishu-hai. A tokkuri is basically a ceramic decanter, which is used for two reasons: one, it allows people to bring enough sake to the table to serve everybody. And two, the fact that it's ceramic means that it can be submerged in piping hot water, which allows for heated sake.

One example of a tokkuri. Image: Wikimedia / Creative Commons

Choko or ochoko are the small ceramic cups that the sake is actually sipped out of. Sakazuki are somewhat similar to choko, although they're shaped much more like shallow bowls rather than little cups.

One example of a choko (ochoko). Image: Flickr / Spiegel

For cold sake, reishu-hai, which are basically the wine glasses of the sake world — usually made of glass but not always — are generally used.

Some fancy, modern sakazuki. Image: Wikimedia / Mori Masahiro Design Studio, LLC.

SAKE SERVING/DRINKING ETIQUETTE

Aside from serving the sake in the proper drinkware, you'll also want to obey the proper drinking/serving etiquette, which is broken down into the five points below: 1. First up, always pour sake for others and never pour sake for yourself — unless you're drinking alone, in which case, don't drink alone, find some friends to drink with you, dang it. 2. When pouring sake for others, you'll want to place two hands on the tokkuri, regardless of its size. If you can only use one hand, place your free hand on the arm that is pouring in order to show respect for the other people at your table. 3. If somebody is pouring the sake into your cup, hold it in the palm of your hand and rest your free hand on the side of the cup. Make sure to lift your cup slightly toward the pourer — again, this is a show of respect.

The respectful way to hold a sakazuki full of sake. Image: Flickr / Connie

4. Keep seniority in mind, especially at business or ceremonial functions. If you're pouring for people who have seniority over you (for one reason or another, whether that be age or status) make sure to strictly obey the other rules on this list. 5. Raise your choko for a toast! Before the start of each sake sesh, make sure you cheer to something. And when you do, say "kanpai!," which is the traditional Japanese way of saying "cheers." If you're around people who have seniority over you, make sure that when you cheer and clink chokos with them, the lip of your cup is lower than theirs. 6. Finally, if you're just drinking among close friends, you obviously don't need to worry too much about these rules. Still though, why not follow them for fun? At least from time to time.BUT WHAT ABOUT SERVING TEMPERATURE?

Now we come to the biggest point of confusion and contention: the temperature at which sake should be served. It seems like a simple matter, almost trivial, in fact, but for some reason this is the part of sake that gets most people — even experienced drinkers — all flustered and defensive. So with that context in mind, here's our best summary of when sake should be served chilled, room temperature, or warm. When it should be served chilled: Generally chilled sake (reishu) is served during during warmer times of the year, such as summer. Low quality sake with relatively pour taste is also usually served chilled, as the low temperature helps to mask the flavor. Chilled sake is usually served 50 °F (10 °C).

A tokkuri full of chilled sake. Image: Flickr / Studio Sarah Lou

When it should be served room temperature: In most instances, high-quality sake is served at room temperature. This is because either chilling or heating sake will change its flavor profile, and why would anybody want to do that with a premium sake? When it should be served warm: As with chilled sake, warm sake (atsukan) is usually season dependent and also used to mask the relatively poor flavor profile of cheaper, lower quality sakes. Obviously warm sake is more suitable for colder seasons, and is generally served at around 120 °F (50 °C).

A bottle of warm sake. Note how warm sake is served in a ceramic vessel, which allows for it to be heated from the outside with hot water. Image: Flickr / Nelo Hotsuma

Note that these are guidelines, not hard-and-fast rules. So feel free to experiment with tasting different sakes at different temperatures — and if you're at a restaurant, don't be afraid to ask the staff what temperature they think is best for whatever sake you're ordering for your table.DRINKING SAKE WITH FOOD

Sake isn't like a fine whiskey or brandy, where it's often best enjoyed on its own without the accompaniment of any kind of food. On the contrary, sake often works best when paired with food. In terms of what foods work best, here are some general guidelines: Japanese cuisine works great with sake. (Mega duh.) Some of the best Japanese foods to try with sake include: ramen, sushi, sashimi, tempura, broccoli gomaae, spicy bean sprout salad, and anything with mushrooms. Needless to say, tons of other Japanese dishes aside from these would also work. https://giphy.com/embed/l1KsrnHJfFr45TeLe Regarding flavor, pair like foods with like sakes. For example, you'll probably want to complement a rich, savory food with a rich, savory sake. For a light dish, like a lean fish or chicken, you'll want to drink a light-bodied sake. Although you can also try contrasting food and sake — for example, try pairing a fruity sake with savory foods like roast beef, fried noodles, sweet and sour chicken, or even pizza. Regarding texture, the same rules as flavor pairing apply. For example, pair a very textured sake with textured foods like pulled pork, steak, or other meats. On the flip side, if you want to contrast, pair textured sakes with less textured foods like udon, miso soup, or bento. Pair acidic sakes with fatty, oily foods. This means that if you'll be eating some raw fish — or really any kind of oily fish — pair it with a highly acidic sake. (Look for a high Aminosan-do level if you want to make sure you're getting a properly acidic sake.)DRINKING SAKE IN COCKTAILS

For sake cocktails, there's a lot of good advice out there from experienced bartenders and mixologists as sake is becoming a more and more popular base liquor for mixed drinks. And while we give you plenty of sake cocktail recipes in the below sections, there are still some general rules of thumb that are great to know. So here are a few good tips to keep in mind: 1. If you're just getting started with your sake exploration, try swapping out vermouth for sake in classic cocktails that call for the former ingredient. 2. Try substituting vodka or gin for sake in cocktail recipes that call for the former spirits. Sake has a lot in common with gin and vodka and should be just different enough to change the flavor profile of the cocktail without ruining it.

The Cucumber Saketini. Image: Tipsy Bartender

3. Avoid using very high-end sakes like Junmai Daiginjo for cocktails. As with many other high-quality spirits, a premium sake is kind of wasted on a cocktail as its more nuanced flavors will be masked by the other ingredients in the drink and go unnoticed. Bartenders and mixologists experienced in the art of making sake cocktails recommend using namazake, the unpasteurized sake, as its fresh, relatively aggressive flavor profile will allow it to stand out enough, but not too much, amongst the other ingredients. 4. It's OK to use premium sakes in cocktails if there aren't too many other ingredients and if those ingredients aren't too overpowering. Something like a Pink Grapefruit, Ginger, and Lemongrass Sake cocktail would be a good example of what to aim for when making a drink using premium sake. 5. Pair sake with herbal and botanical spirits such as gin, Cyner, or Chartreuse. The melon and grass flavorings of sake will complement these types of spirits well, and it can even be added in relatively small amounts just to serve as a way to round out the flavors of the other herbal spirits.HOW TO STORE SAKE

Alright alright alright, you now know what sake is, where it came from, how it's made, and all of its different categories, which means you know everything you need to know about it, right? Wrong! You also need to know how to store it properly. So to finish out your sake knowledge, here are the basics in regards to how to store this traditional Japanese spirit.KEEP IT IN A COOL, DRY PLACE AWAY FROM LIGHT

As with all other liquors, you'll want to store your sake in a cool, dark, dry place. Yes, we know this is some ultra-basic advice, but we know some of you out there need to be reminded that your booze bottles should not sit out in direct sunlight — treat them like succulents, dang it! You'll also want to make sure that the sake is stored away from anything that vibrates — e.g. a washing machine — as that jostling could cause the sake to mix around and have its flavor dulled. Double also: Sake bottles, unlike wine bottles, should be stored upright rather than on their side — you don't want your sake frequently coming into contact with the sake cap.REFRIGERATE UNPASTEURIZED OR SINGLE-PASTEURIZED SAKES

If you have yourself some namazake or another unpasteurized sake, make sure you store it in a refrigerator! Seriously, don't put this stuff in your old, dusty liquor cabinet — it will go bad. Aside from namazake, you'll also want to keep your junmai, daiginjo, and ginjo sakes in the fridge as well. Also, if the bottle of sake says "store in the refrigerator," store the sake in the dang fridge! That label is not messing around.

A fridge full of unpasteurized sake. Image: Flickr / halfrain

KEEP SAKE IN ITS CASE IF IT WON'T BE DRUNK SOON

Finally, in regards to storage, if you have a bunch of sake bottles that you don't plan on drinking anytime soon — and they're not unpasteurized! — you should keep them in their cases. Not only do the cases help to further protect the sake against harmful UV light (and make for an easier time moving the sake around), they also have the "drink by" designations on them, which means you can keep all the sakes that should be drunk in the same timeframe together.THE FUTURE OF SAKE

OK, before you're done with this little sake 101, we need to talk just a bit more about where sake is headed, that way you know what to expect when it comes to building your future home (or professional) bar. And honestly, you may want to get your hands on some high-quality sake ASAP 'cause there's a pretty good chance you'll actually be seeing less of it in stores and/or restaurants in the coming years. Although despite this somewhat pessimistic outlook on the future of sake, there's still a good chance it'll be increasing in popularity — at least somewhat in the rest of the world — especially amongst craft cocktail makers.

A Japanese bar loaded up with sake. Image: Flickr / Maarten Heerlien

The reason sake seems to be gaining a modicum of popularity in countries outside of Japan — as opposed to Japan, where sake faces a precipitous decline in popularity — is that there is an expanding interest in Japanese food worldwide. In fact, in the last five years the number of Japanese restaurants in existence throughout the world has doubled from 55,000 to 110,000. These Japanese restaurants, of course, stock plenty of sake, which means more and more people outside of Japan are being exposed to it. Despite the boost in popularity from Japanese restaurants, sake still faces a painful, uphill battle when it comes to turning things around in Japan. The spirit's sales have been steadily declining year after year and its image in the mainstream is one of being an outdated booze only drunk by the older generations. On top of this perception of sake being a drink for the elderly, young Japanese people aren't encouraged to get into the business because it's daunting and requires a massive sacrifice of time and freedom. Sake production also takes place in more rural areas, and young Japanese people are flocking to, and staying in, the big cities.

A toji checks on the rice after it's been steamed. Will the career path of the toji become obsolete? Image: Flickr / tokyofoodcast

It's still hard to say for sure how things will play out in the future for sake though. There are still big brands and small craft makers in the game, and they're going to do everything in their power not only to grow sake's popularity abroad, but also try to bring it back to life in Japan. Until that happens, make sure to grab yourself at least a couple of bottles of different varieties for your home bar — nothing's cooler than doing something that isn't cool anymore right?EIGHT OF OUR FAVORITE SAKE DRINKS

1. THE BLOODY GEISHA 2. CUCUMBER SAKETINI

2. CUCUMBER SAKETINI

3. JAPANESE LONG ISLAND

3. JAPANESE LONG ISLAND

4. MATCHA MAN SOUR

4. MATCHA MAN SOUR

5. SAKE BOMB

5. SAKE BOMB

6. SAKE TO ME MARGARITA

6. SAKE TO ME MARGARITA

7. SAKETINI

7. SAKETINI

8. TOKYO DRIFT

8. TOKYO DRIFT

GIFs: Giphy

Independence Day Drinks

4th Of July All American Jello Shots

4th Of July Cake Vodka Milkshake

4th Of July Diversity Bomb Shot

4th Of July Jello Shots

4th Of July Layered Shots

4th Of July Pop Rocks Martini

4th Of July Raspberry America

4th Of July Spiked Bomb Pops

4th July Popsicle Margarita

4th July Edible Shot Glasses

4th July In A Bottle

All American Daiquiri